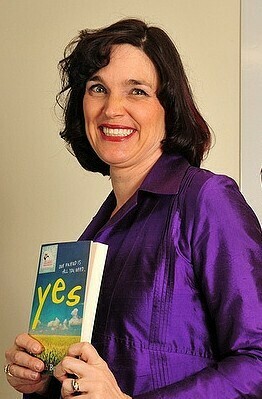

Patricia Grace

Patricia’s books (6)

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Grace, Patricia (1937– ), novelist, short story writer and children’s writer, is of Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Awa descent, and is affiliated to Ngāti Porou by marriage. She has gained wide recognition as a key figure in the emergence of Māori fiction in English since the 1970s (see also Heretaunga Pat Baker, Keri Hulme, Witi Ihimaera, Bruce Stewart, June Mitchell). Her work, expressive of Māori consciousness and values, is distinguished also for the variety of Māori people and ways of life it portrays and for its resourceful versatility of style and narrative and descriptive technique.

Born in Wellington, Grace was educated at St Anne’s School, St Mary’s College and Wellington Teachers’ Training College, later gaining Victoria University’s Diploma in the Teaching of English as a Second Language. At Teachers’ College, she began to seek out books by New Zealand authors, including Frank Sargeson, Janet Frame and Amelia Batistich: ‘when I first read some of her stories it came home to me [that] writing was a question of voice and truth, and of a writer finding his/her own way of telling. Grace was a New Zealander with a different voice’ (interview with Jane McRae in In the Same Room, ed. Elizabeth Alley and Mark Williams, 1992). She began writing at about 25 while teaching in North Auckland, being published in Te Ao Hou and the NZ Listener, and continued to write while teaching, raising her family of seven children and moving to Plimmerton, near Wellington, where she still lives. Her first book, Waiariki (1975), the first short story collection by a Māori woman writer, won the PEN/Hubert Church Award for Best First Book of Fiction.

The collection is shaped so as to find for Māori, in the words of the first story’s title, ‘A Way of Talking’, and to ‘show who we are’. This is the task given by an elder to the narrator of the final story, ‘Parade’, and stands almost as an artistic credo. The collection may be read as a progress from the almost autistic inarticulateness of the schoolgirl Hera in ‘A Way of Talking’ to the confident choric harmony of the canoe chant in Māori with which ‘Parade’ ends.

The opening and closing of the volume thus establish a meticulous though unobtrusive patterning: this careful craft remains characteristic. The ten stories between elaborate the affirmation of a people’s right to speak, each with a narrative voice that is distinctively different, yet distinctively Māori, whether formally oratorical or racily colloquial. Though Grace’s style has often been described merely as ‘simple’ or ‘lyrical’, she has successfully shown that ‘a Māori world is not limited and Māori people are as diverse as any other people.’ While not the only writer to make narrative use of the Māori oral tradition, Grace’s sheer range is instantly impressive.

She has continued to extend it. Her first novel, Mutuwhenua: The Moon Sleeps (1978), tells the story of the love and marriage of a young Māori woman and Pakeha man, the first time this had been done from the Māori perspective and by a Māori writer. It is focused on the effort of Ripeka/Linda to find identity as well as love, as increasingly she commits herself to her Māori being, family and name.

The novel ends with her passing the couple’s baby to her mother to be brought up in the extended family, so that the effort of what Grace has called the ‘very, very large leap’ of cross-cultural adjustment is asked of the husband, whereas ‘Most often it’s the Māori people who have to go across the gap’ (McRae interview). His love and moral quality are tested and judged in those terms: ‘I went to him confidently. He had not once failed to love.’

While committedly Māori, Mutuwhenua is pointedly positive and non-polemical, emphasising ‘the common ground that all forms of life have in this country,’ with ‘stereotypes skilfully flicked aside’ (Patrick Evans, Landfall 128, 1978). Its writing also demonstrates a remarkably sensitive ear, with phrases often cadenced and paragraphs almost scored musically, for instance in the rhythmic Eliot-like prose poems which describe the city, or the several evocations of the sea shore. (Every Grace book has included variations on this aural depiction of the sea meeting the land.)

Grace is acutely conscious of sound, subtle in onomatopoeia, and imbues even visual description with a strong aural quality. The stories in The Dream Sleepers and Other Stories (1980), her second collection, extend the diversity of Māori voices and aspects of Māori life, including some robustly sketched children and two memorable mothers—the comic-maverick car-toting mother of ‘It Used to be Green Once’ and the elemental, mythic yet very human mother of ‘Between Earth and Sky’, a three-page monologue which has rapidly become an iconic New Zealand text.

Always writing well of children, Grace in the early 1980s wrote increasingly for them, seeking to add to the ‘few stories that Māori children see themselves in and that reflect their lives.’ The Kuia and the Spider / Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere (1981), illustrated by Robyn Kahukiwa, which tells of a spinning contest between the elderly Māori woman and the spider of the title, won the Children’s Picture Book of the Year Award. Watercress Tuna and the Children of Champion Street / Te Tuna Watakirihi me Nga Tamariki o te Tiriti o Toa, also illustrated by Kahukiwa, emphasises society’s multiculturalism, and was also published in Samoan. Grace has also published a third children’s book, The Trolley (1993) and several Māori language readers, Areta and the Kahawai/ Ko Areta me nga Kahawai (1994).

The collaboration with Robyn Kahukiwa then produced Wahine Toa (1984), Grace’s text complementing the book-form reproductions of Kahukiwa’s striking paintings of the women of Māori mythology. ‘We decided to personalise the stories realising more and more that the stories are both contemporary and ancient.’

In 1985 Grace held the Victoria University writing fellowship, gave up teaching and completed her second and most successful novel, Potiki (1986), which won the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction and was third in the Wattie Book of the Year Award. In many ways, it is a synthesis of the skills developed in the earlier work (including the children’s writing), with carefully crafted cadences and aural effects unifying the prose, and evoking not only the people’s diverse individual voices and the sounds of their environment but their harmony with it and each other.

Potiki has been translated into several languages and in 1994 won the LiBeraturpreis in Frankfurt, Germany.

The more aggressive political stance struck many reviewers, John Beston commenting that Pakeha readers find themselves charged ‘not with past and irremediable injustices, but with continuing injustices’ (Landfall 160, 1986). Their embarrassment (in Hera’s word from ‘A Way of Talking’) extends to the inclusion of much untranslated Māori, especially the ending, and the absence of a glossary. In Potiki as earlier in ‘Parade’ Grace disempowers the reader who can read no Māori at crucial points within the cultural form of fiction in English. Potiki makes more evident how subtly subversive a writer she habitually is.

Her third collection, Electric City and Other Stories (1987), adds to the group of stories in The Dream Sleepers, centred on the girl Mereana, which Grace originally thought ‘would add up to a novel, but they didn’t’. The volume’s more successful stories are the darker adult ones, such as ‘Hospital’, with its harsh, hallucinatory version of childbirth and surgery, and its close on a despondent and aimless journey (‘not to know what’s round this bend, the next, the next one after that’), thus ending where Cousins begins.

Grace’s third novel, Cousins (1992), followed Selected Stories (1991). In what may now be seen as a characteristic shaping principle, it moves from that initial wandering journey, silent, blind and objectless, to the vocal, visionary, firmly rooted communal harmony of the ending, with its sense of membership and continuity even in the face of death.

The Sky People (1994), her fourth story collection, is more explicitly and consistently concerned with the disoriented, dispossessed and despondent—‘The Haurangi, the Wairangi, the Porangi—those crazy from the wind or what they breathe, those crazy from water or what they drink, those crazy from darkness or depression’ (prefatory epigraph from ‘conversation with Keri Kaa’).

From sisters damaged by childhood abuse by their famous and respected father to a teenage boy tipped into suicide by sexual jealousy and its consequences, these stories refute any suggestion that Grace sentimentalises relationships among Māori. Some are political, like the zestful Swiftian satire ‘Ngati Kangaru’ (in which Māori from Australia reverse colonisation by appropriating a luxury weekend residential development), some are half-jocularly mythical, like the racy retelling of Māori creation myth in ‘Sun’s Marbles’, and some are realistic and sympathetic sketches of people on the margins of society.

The writing is versatile and self-assured, and the stories stronger and more often surprising than before; several (‘Flower Girls’, ‘The Day of the Egg’, ‘My Leanne’) end with a dramatic twist or punch. The title story, about a group of people who live by re-making rejected clothes in a Wellington attic, shows a developed skill in combining entertaining storytelling with a telling underlying significance.

It also (with others in this collection and earlier) illustrates a paradox that frequently sustains Grace’s art—stories of loss, isolation and sadness which yet are bright with colour, stories where the details of life’s sights and sounds tumble out in vivid lists, and where a childlike innocence and insight intersect with the most knowing adult awareness.

Patricia Grace has won enthusiastic recognition among non-Māori readers, was awarded the Queen’s Service Order in 1988 and an honorary DLitt of Victoria University in 1989. She makes a significant early statement of her artistic aims in Tihe Māori Ora, ed. Michael King (1978). Significant critical discussion includes Rachel Nunns, Islands 26 (1979), John Beston, Ariel 15 (1984), W.H. New, Dreams of Speech and Violence (1987), Mark Williams, Journal of New Zealand Literature 5 (1987), the OHNZLE, ed. Terry Sturm (1991), and Roger Robinson in The Commonwealth Novel in English Since 1965, ed. Bruce King (1991), and the Centre for Research into New Literatures in English Reviews Journal (New Zealand issue, 1993), which also reprints the interview with Jane McRae.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

In 1986, Patricia Grace published her novel Potiki, within which she discusses issues surrounding settler land appropriation and the preservation of the Māori culture. Grace was awarded third place for Potiki at the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Awards, and in 1987, the novel won the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction.

The Trolley, written by Patricia Grace and illustrated by Kerry Gemmill, picked up the 1994 Russell Clark Award for Illustration.

Baby No-Eyes (1998) is a novel that merges controversial actual events with heartfelt family history, using different voices to interweave family mysteries with contemporary Māori issues. Among these voices are those of a deceased baby who becomes a ‘real’ person in order to interact with family members, and Granny Kura, who tells her story against a background of land occupation.

In Patricia Grace’s novel Dogside Story (2001), the power of the land, the strength of whānau, and the aroha of the community are powerful life-preserving factors. As the narrative unfolds, however, it becomes apparent that there is conflict within the whanau, which reaches breaking point as the new Millennium approaches. Dogside Story won the 2001 $15,000 Kiriyama Pacific Rim Book Prize for fiction, an award that was announced at the 14th Annual Vancouver International Writers Festival in Canada.

Dogside Story's run of critical acclaim continued in 2001, when it was longlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize. It was also shortlisted in the 2002 Montana New Zealand Book Awards. Dogside Story was reissued by Penguin Books in 2005. Kelly Ana Morey reviewed that, in Dogside Story, Grace had created ‘...a magnificent hui of a book that bubbles over with laughter, human frailty, hope and love’ (NZ Listener).

Patricia Grace's next novel was Tu, published by Penguin in 2004. With this narrative, Patricia Grace explores the often terrifying and complex world faced by men of the Māori Battalion in Italy during the Second World War, drawing on the war experiences of her father and other relatives to write an authentic fiction about Māori soldier Tu. As the sole survivor of his family’s campaign, Tu must come to terms with what really happened as the Battalion fought in the hills and valley of Italy – and the truth is contained within the pages of his war journal. The novel received the Deutz Medal for Fiction and Montana Award for Fiction at the 2005 Montana New Zealand Book Awards. It also won the 2005 Nielsen Book Data New Zealand Booksellers' Choice Award.

Patricia Grace was honoured as a living icon of New Zealand art as part of the second biennial Arts Foundation of New Zealand Icon Awards in 2005.

She also wrote 'Moon Story' for the anthology Myths of the 21st Century (Reed, 2006).

In 2006, Grace was awarded $60,000 for fiction at the Prime Minister's Awards for Literary Achievement. Prime Minister Helen Clark said, 'Patricia Grace’s work has played a key role in the emergence of Māori fiction in English. A writer of novels, short stories and children’s fiction her work expresses Māori consciousness and values to a wide international audience.' The annual Prime Minister’s Awards for Literary Achievement recognise writers who have made a significant contribution to New Zealand literature.

As part of the Queen's Birthday Honours list in 2007, Grace received a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to literature.

Grace was named the 2008 laureate of the US$50,000 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. The honour, administered by the University of Oklahoma and its international magazine World Literature Today, is judged by an international jury and widely considered to be the most prestigious international literary prize after the Nobel. In announcing the 2008 Neustadt laureate, Robert Con Davis-Undiano, Neustadt professor and executive director of World Literature Today said: ‘This award is a landmark recognition of an indigenous writer and gives a strong sense of the direction of important literature in the 21st century.’

Grace beautifully writes a true story of love in wartime and in peace in Ned and Katina (Penguin, 2009).

Patricia Grace was the 2014 Honoured New Zealand Writer at the Auckland Writers Festival.

Grace's novel Chappy - her first novel in ten years – was released in 2015. It follows the story of a young man (Daniel) who is sent back to New Zealand to reconnect to his Māori culture and ancestry. In Aotearoa, he discovers his ties to a Japanese grandfather (Chappy), to his local whānau, and to other Pacific peoples, making Chappy a powerful demonstration of the ties that Māori have with the wider world. The novel was a fiction finalist in the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Haka and Whiti te Rā! were published by Huia Press in September 2015. Haka is Grace's retelling of the story of the great Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha and how he came to compose the haka 'Ka Mate, Ka Mate'. It was also released in a te Reo edition, Whiti te Rā!, translated by Kawata Teepa. Both editions are illustrated by Andrew Burdan. Haka was a finalist for the Picture Book Award and Whiti te Rā! won the Te Kura Pounamu Award at the 2016 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.

Grace's novel Cousins was made into a feature film in 2021, directed by Ainsley Gardiner and Briar Grace-Smith, with a screenplay by Briar Grace-Smith.

Grace's memoir From the Centre: A writer's life was published in May 2021 by Penguin Random House, and followed by a book of short stories, Bird Child & Other Stories, in January 2024.