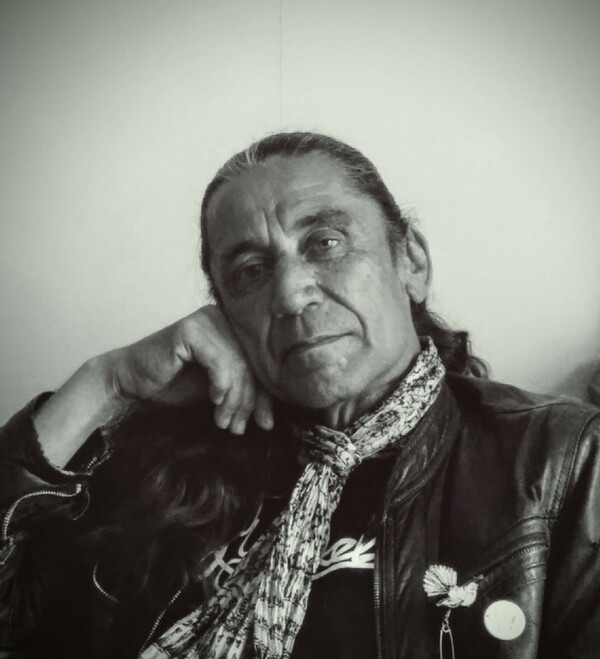

Keri Hulme

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Hulme, Keri (1947–2021), novelist, short story writer and poet, gained international recognition with her award-winning the bone people. Within New Zealand, she held writing fellowships at several universities, served on the Literary Fund Advisory Committee (1985–89) and the Indecent Publications Tribunal (1985–90), and in 1986–88 was appointed ‘cultural ambassador’ while travelling in connection with the bone people.

Born and raised in Otautahi, Christchurch, Hulme is the eldest of six children. Her father, a carpenter and first-generation New Zealander whose parents came from Lancashire, died when Hulme was 11. Her mother came from Oamaru, of Orkney Scots and Māori descent (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe). Hulme was schooled at North New Brighton Primary School and Aranui HS (Christchurch). Her holidays were spent with her mother’s extended family at Moeraki, on the Otago East Coast, a landscape filled with the residue of its Māori past, which remained important for linking Hulme with her Māori ancestors: ‘I love it better than any place on Earth. It is my turangawaewae-ngakau, the standing-place of my heart.’ Partial accounts of her childhood are in ‘Okatiro and Moeraki’ in Te Whenua, Te Iwi/The Land and The People (ed. Jock Philips, 1987) and Homeplaces: Three Coasts of the South Island of New Zealand (words by Hulme, photographs by Robin Morrison, 1989). Hulme remembered that as a child she was possessed of ‘a relish for telling stories and an obsessive desire to communicate’. After her father’s death, the sun-porch of the family home was turned into a study for the young writer; she recalled rewriting Enid Blyton stories the way she thought they should have been written, writing poetry from the age of 12, and composing short stories, a few of which were published in school magazines.

After leaving school, Hulme shunned university and worked instead as a tobacco picker in Motueka. It was here, aged 18, that she had the first of many dreams about a mute, long-haired, grinning child with strange, green eyes, from whom the name Simon Peter ‘seemed to resonate.' She began to write about him in a short story, ‘Simon Peter’s Shell’. In the course of the next seven years, the child continued to appear in Hulme’s dreams; notes, drawings and stories about him, and other allied characters, accumulated. These fragments eventually formed the basis of her novel the bone people, which was published in 1983, more than seventeen years after the first dream-appearance of Simon Peter. In 1967 Hulme began an honours law degree at Canterbury University, but left after four terms, returning to tobacco picking. By 1972, at 25, she was obsessively reworking her dream material and associated drawings and stories: ‘I had a kind of theatre going on in my head each night and it was getting out of control.’ She decided to turn her hand to writing full-time in order to make sense of the mass of material she had accumulated but despite family support survived only nine months before poverty again forced her to undertake an ‘endless stream of menial jobs’, in Woolworths, as fish-and-chips cook, woollen-mill winder, postie, journalist and television production trainee. Hulme continued to write and publish poems and stories in journals, magazines and anthologies. Some of her earliest work appeared in Lost Voices (1979) under the pseudonymn of Kai Tainui, who also made a brief appearance in Landfall 138 (1981) with the story ‘A Nightsong for the Shining Cuckoo’. ‘Nightsong’ subsequently appeared in Hulme’s collection of short stories, Te Kaihau/The Windeater. Despite a fairly small output, Hulme won several awards for her writing, including the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Award for her short story ‘Hooks and Feelers’ (1975), the Māori Trust Fund Prize (for writing in English; 1977), the ICI Writing Bursary (1982) and the New Zealand Writing Bursary (1983). In her first collection of poetry, The Silences Between (Moeraki Conversations) (Auckland University Press, 1982), six ‘conversations’ are separated (or linked) by pieces called ‘silences’. Together, these comprise a kind of poetical dream diary, recording the thoughts, memories and actions of a central persona, which it seems natural (if mistaken) to assume is Hulme herself.

Throughout these years, Hulme continued to work on the material which had its origins in the dreams, gradually shaping it into a novel. Linked to the figure of the child, other characters appeared in her dreams and writing, notably Kerewin Holmes and Joe Gillayley, who, together with Simon form the triad at the centre of the bone people. Hulme has said of Kerewin that although she ‘has always been a bit of an off-shoot of me—a sort of wish-fulfilment character for what she owned, a shallow alter ego’, nonetheless ‘she escaped out of my control and developed a life of her own’. Eventually a first draft of the novel was completed and submitted. The first publisher’s response was to prove characteristic, suggesting that the manuscript be trimmed by about half. Hulme’s mother helped edit out unnecessary material from the first three chapters and Hulme continued to rework the manuscript, offering it to a variety of publishers and eventually rewriting it seven times. (Some of this manuscript material has been deposited at the Hight Library, University of Canterbury; two further draft manuscripts are in the possession of Hulme’s mother and another three have been kept by the writer.) Four publishers refused the novel in its submitted form, apparently for different reasons. It was not only the intrinsic Māori elements of the novel and its stylistic experimentation that were a problem. Several more publishers recommended severe editing but Hulme adamantly refused to allow anyone to ‘go through [her] work with shears’ or be ‘a silent partner’ in her work. The novel was finally accepted by the Spiral Collective and published with the assistance of two Literary Fund grants. Typeset by members of the Victoria University Students’ Association, and proofread and pasted up by members of the collective, the first edition of the novel is striking for, if flawed by, a remarkable lack of editorial intrusion and the idiosyncrasies of its many typographic errors. It was launched with a hui at Wellington Teachers’ Training College in February 1984. Extremely well reviewed, copies of the small first print run, and the second, sold out very quickly. The novel was awarded the Mobil Pegasus Award, allocated that year to Māori fiction (1984) and the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction (1984). A new edition, jointly published by Spiral and Hodder and Stoughton, appeared in 1985 and went through several print runs; Louisiana State University Press published the first American edition. That year the bone people was awarded the prestigious international Booker Prize.

Hulme acknowledges the need to respect all facets of her ancestry. Māori, Celtic and Norse mythology, in homage to her mixed heritage, is threaded through all of her writing, as are fragments of Māori language, and allusions to European (notably English and Irish Modernist) writing and a variety of inherited narrative conventions. However, she has on numerous occasions declared herself to be wholly Māori by spirit and inclination: ‘I think of myself as a Māori writer rather than Pakeha that’s the strong and the vivid and the embracing, the good side of things. That’s where I draw my strength from.’ She has time and again defended her right to identify and write as Māori, despite criticism which undermines the ‘authenticity’ of this identification. Most notorious is C.K. Stead’s Ariel article (1985) in which, while praising the ‘imaginative strength’ of the bone people, he criticises Hulme’s receipt of the Pegasus Award for Māori writers. Stead suggests that the Māori elements of the novel are ‘willed, self-conscious, not inevitable, not entirely authentic’, arguing that as Hulme is only one-eighth Māori, her upbringing was substantially European and she was raised speaking English, she has no right to write as and for Māori. Hulme has never made any public response to Stead’s criticism.

The bone people was followed by a collection of poems, Lost Possessions (Victoria University Press, 1985) and a collection of short stories Te Kaihau: The Windeater (Victoria University Press, 1986). Both have received very little critical attention. In 1987, Hulme was awarded the Chianti Ruffino Regional Award and in 1989 published Homeplaces, her homage to Okarito, Moeraki and Stewart Island. A further collection of poems, Strands, was published in 1992 (Auckland University Press). Many critics have commented on the deeply negative nature of Hulme’s writing, despite her wry humour and the celebration in her work of what she calls the ‘good things’ in life: fishing, cooking, eating, drinking, playing the guitar and painting. Arguably, it is this which accounts for the popular and critical success of the bone people and the somewhat ambivalent and muted response to the other writing. The novel manages to contain its negativity, at least for the imaginative duration of the fiction, concluding with an optimistic reconciliation of the (cultural, ethnic, interpersonal and narrative) tensions played out in the fiction. In the short stories and poetry, however, these tensions are laid bare for the reader; redemptive resolution is rarely, if ever, achieved. Critics have tended to read many of the characteristic aspects of Hulme’s writing in terms of her situation as a postcolonial writer. Her negativity is often read as reflective of her ambivalent and pessimistic appraisal of New Zealand’s ‘postcolonial crisis’ in which Pākehā and Māori struggle to negotiate differences in the attempt to forge a new bicultural identity. Hulme’s postcoloniality, it is argued, accounts for her persistent use and subversion of binary categories (whether Māori/Pākehā, male/female, realism/fantasy or life/death) and her celebration of multiplicity. Similarly explained is the cultural eclecticism of her writing, its multiple literary, linguistic and religious/mythic sources; and her linguistic experimentation is interpreted as attempts to merge and meld both English and Māori into a new language capable of expressing (postcolonial) experience. Other critics have read Hulme’s work in terms of its feminism, although Hulme is typically ambiguous in her response to such readings: ‘I’m a feminist because I was born female but I’ve never belonged to a feminist group in my life.’

A self-styled neuter, like her character Kerewin, Hulme lives alone in the octagonal house she built in Okarito, on the West Coast of the South Island, where she engages her creativity (writing, painting and drawing) for nine months of the year; the other three months are spent entertaining family. She writes from the main room of her home which overlooks the Tasman Sea—the importance of this coast, too, to Hulme has been reaffirmed in numerous interviews and throughout her writing. Her twinned novels Bait and On the Shadow Side, on which she has been working for a number of years, are awaited.

Correction note: Keri Hulme has responded publicly to C. K Stead's Ariel article (1985), and she has said, 'The judges for the Mobil Pegasus Award for Māori writing in New Zealand were MAORI, in good standing both academic and otherwise. C.K. Stead presumes to know better than them. He is wrong, on all counts.'

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

In 1977, Keri Hulme received the Bank of New Zealand Katherine Mansfield Short Story Award. In the same year, she shared the Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago with Roger Hall.

In 1986, she was awarded third place for Te Kaihau/The Windeater at the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Awards.

the bone people (Spiral Collective, 1984) won the 1984 New Zealand Book Award for Fiction, and the prestigious international Booker Prize in 1985. 'Set on the harsh South Island beaches of New Zealand, bound in Māori myth and entwined with Christian symbols, Miss Hulme's provocative novel summons power with words, as a conjuror's spell. She casts her magic on three fiercely unique characters, but reminds us that we, like them, are 'nothing more than people', and that, in a sense, we are all cannibals, compelled to consume the gift of love with demands for perfection' (New York Times Book Review).

Keri Hulme's second collection of short stories, Stonefish, was published by Huia Publishers in 2004.

Her novella 'Te Kaihau/The Windeater' appears in Nine New Zealand Novellas, edited by Peter Simpson (Reed, 2005). This is a companion volume to Seven New Zealand Novellas.

the bone people was selected as the 2014 Great Kiwi Classic.

In 2014, Hulme gave her last interview for the New Zealand public on news show Campbell Live.

Keri Hulme died in Waimate on 27 December 2021, at the age of 74.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Writing by Keri Hulme on the New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre site

- Booker Prize profile

- In Memory of Keri Hulme by Kelly Ana Morey, Academy of NZ Literature