James K. Baxter

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

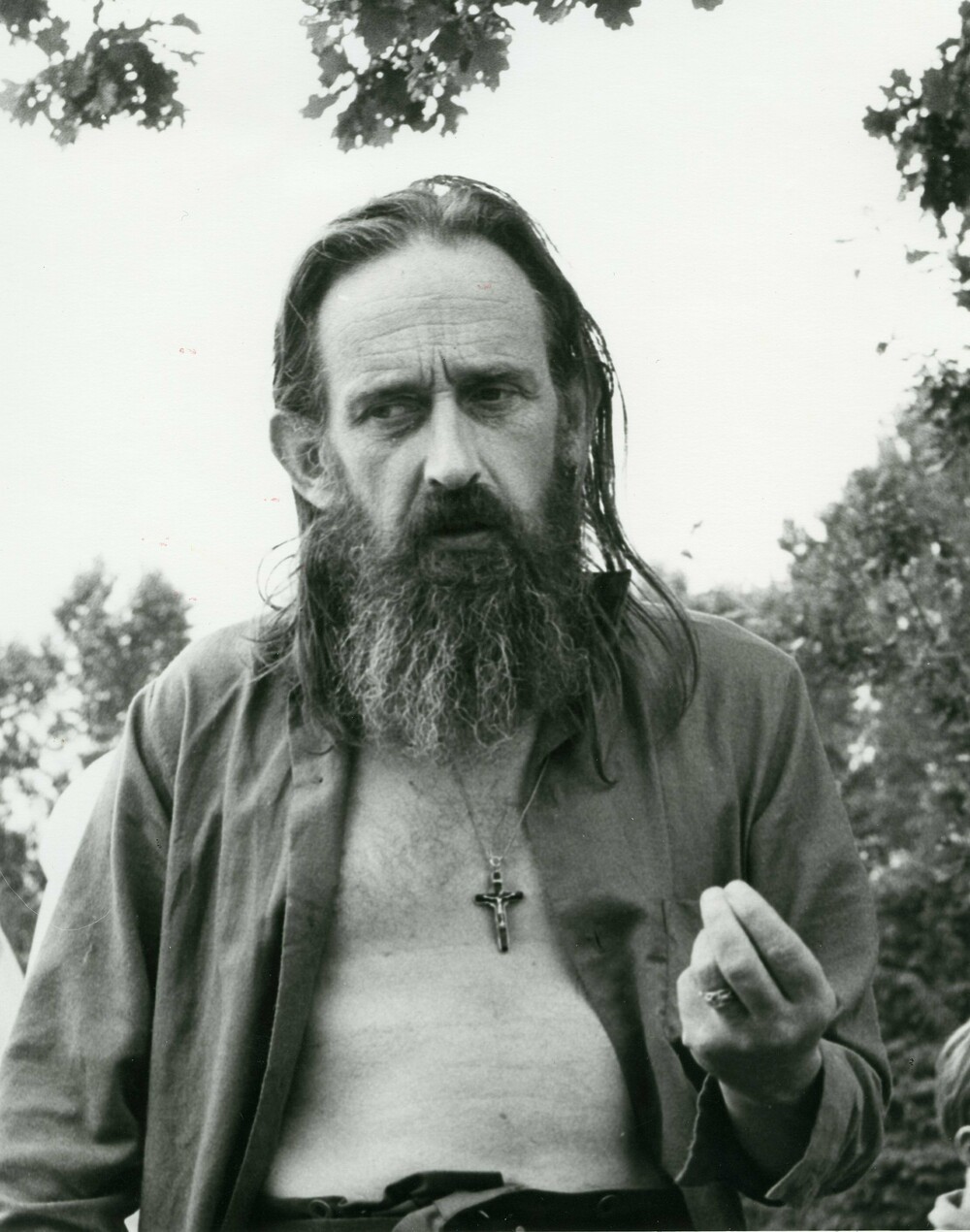

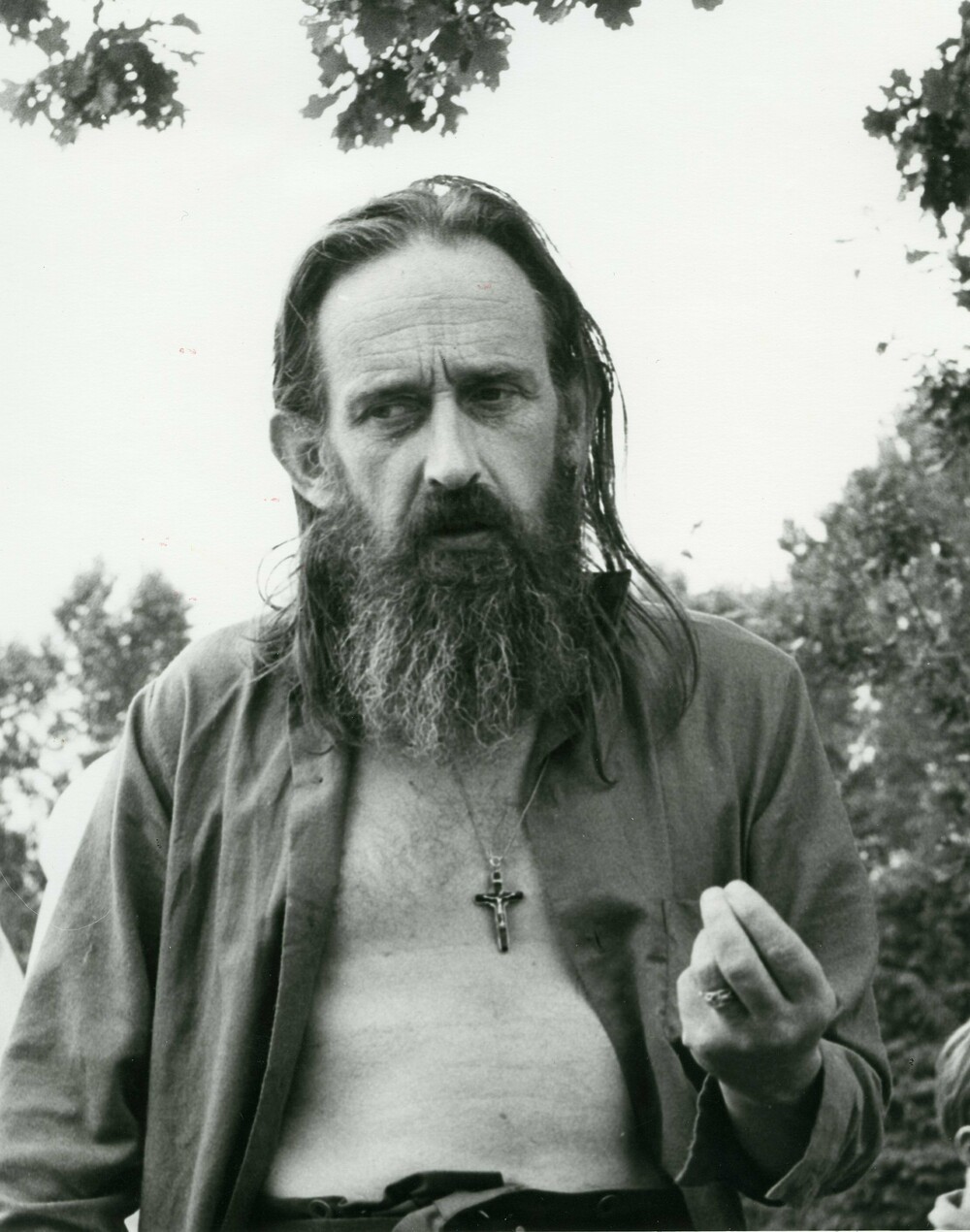

Baxter, James K. (1926–72), poet, dramatist, literary critic, social commentator, was born in Dunedin into an Otago farming family. Family fable has it that Archibald Baxter prayed that he ‘might have a poet for a son’. James, the second son, indeed became one of New Zealand’s finest poets and most controversial figures, often at odds with a society unable to stomach its disturbing reflection in his work.

James Baxter (known by friends as ‘Jim’ or, later, ‘Hemi’) once described each of his poems as ‘part of a large subconscious corpus of personal myth, like an island above the sea, but joined underwater to other islands’, and elsewhere commented that what ‘happens is either meaningless to me, or else it is mythology’. This tendency to mythologise his life in verse makes biography important in any response to his poetry.

Baxter’s middle name—after the Scottish socialist, Keir Hardie—signified his parents’ left-leaning politics. Their beliefs profoundly influenced him, as did their contrasting backgrounds. Whereas the quiet Archie’s ancestors had been small-farmers in the Scottish highlands, Millicent was the strong-minded eldest daughter of the distinguished Professor John Macmillan Brown, who mistakenly regarded the marriage as a mismatch. Baxter’s aversion to systematic schooling was symbolised by an incident on his first day at Brighton Primary School, on Otago’s coast, when he burnt his hand. As the family moved, he later attended Quaker schools in Whanganui and the English Cotswolds, and, in World War II, King’s HS in Dunedin.

This was not a good period for pacifists. The family was suspected of spying, James was bullied, and his brother Terence sent into detention as a military defaulter. Adolescence was therefore a solitary time, but Baxter felt that his experiences ‘created a gap in which the poems were able to grow’. Indeed, between 1942 and 1946 he drafted some 600 poems.

An able although unmotivated student, Baxter matriculated a year early, with unspectacular results, applying himself meanwhile to reading and imitating almost the entire English poetic canon. The moderns, particularly Auden, Spender, MacNeice and Day Lewis, inspired him with the voice they were giving to the social battles of the time. By his late teens, a discernible voice was developing out of adolescent imitation.

In 1944, Baxter began a ‘long, unsuccessful love affair with the Higher Learning’ when he enrolled at Otago University. ‘Incipient alcoholism’ soon became a problem, but in 1944 he won the Macmillan Brown literary prize (for ‘Convoys’) and Caxton Press published his first collection, Beyond the Palisade, to critical acclaim. Six poems from Beyond the Palisade were selected for Allen Curnow’s A Book of New Zealand Verse 1923–45. A second book, Cold Spring, remained unpublished at that time

Abandoning university study, from 1945 to 1947 Baxter worked in factories and on farms. Part of this period is fictionalised in his novel Horse (1985). His struggle with alcoholism was both cause and consequence of the failure of his first significant love affair, with a young medical student. Her enduring effect, however, is evident in three poem sequences: ‘Songs of the Desert’ (c.1946–47), ‘Cressida’ (1951) and ‘Words to Lay a Strong Ghost’ (1966). An even more important relationship began in 1947 when he met Jacqueline Sturm.

In late 1947 Baxter moved to Christchurch, ostensibly to renew his university studies, but actually to visit a Jungian psychologist. He began incorporating Jungian symbolism into his poetic theory and practice. His behaviour, thanks to the ‘irrigating river of alcohol’, could be erratic as he sporadically attended lectures and took jobs as a sanatorium porter, copy editor for the Christchurch Press and freezing worker. He began associating with the poets Curnow and Glover, and his reading remained copious.

Blow, Wind of Fruitfulness (1948) confirmed Baxter as the pre-eminent poet of his generation. His interest in religion culminated in baptism as an Anglican, and, despite considerable parental concern, he and Jacquie were married in St John’s Cathedral, Napier.

Moving to Wellington, they enrolled at Victoria University College and associated with the generation of writers that included Bill Oliver, Alistair Te Ariki Campbell and Louis Johnson, and became known as the Wellington Group.

In 1951, now attending Wellington Teachers’ College, Baxter enthralled the New Zealand Writers’ Conference with his lecture Recent Trends in New Zealand Poetry, subsequently published by Caxton. One reviewer described him as ‘the profoundest critic we have’. A selection of poems in a collaborative volume, Poems Unpleasant, was published in 1952. Having completed his Teachers’ College course, Baxter studied full-time at Victoria University in 1953, also publishing The Fallen House. In 1954 he was assistant master at Lower Hutt’s Epuni School. An able teacher, but no disciplinarian, his major contribution was a series of children’s poems published posthumously as The Tree House (1974). Also in 1954, he gave three Macmillan Brown lectures on poetry at Victoria University, published, to mixed reviews from critics concerned by his simplification of issues and reliance upon anecdote, as The Fire and the Anvil (1955).

In late 1954, Baxter joined Alcoholics Anonymous, espousing its principle of helping others in a course of counselling and prison visitation that continued for the rest of his life. Some stability was achieved partly through a substantial legacy with which the family purchased a house in the Wellington suburb of Ngaio. He received his BA in 1955 and published a long poem in pamphlet form, Traveller’s Litany. He left Epuni School in 1956 to work for School Publications, a period which provided material for numerous attacks on bureaucracy.

Baxter discovered the pitfalls of parody when his skilful imitations of seventeen New Zealand poets, The Iron Breadboard: Studies in New Zealand Writing (1957), was received with acrimony by some of his peers. Fourteen more serious poems appeared in a collaboration, The Nightshift: Poems on Aspects of Love (1957), a collection that, to quote Howard McNaughton, ‘established a position of alienation that would recur in his work for two decades’. The following year Baxter received international recognition when Oxford University Press published In Fires of No Return. Critics, however, thought the book loose and poorly selected. Baxter’s greatest success in 1958 was the radio play, broadcast in September, Jack Winter’s Dream. The script was published in Two Plays: The Wide Open Cage and Jack Winter’s Dream (1959), adapted for the stage in 1960, and filmed in 1979. Domestically, things were less successful. Jacquie was astonished by Baxter’s unheralded decision to convert to Roman Catholicism and in October 1957 they separated. He was received into the Church in 1958.

A UNESCO Fellowship to study educational publishing in Japan and India gave Baxter and Jacquie a chance to reconcile. He left for Japan in September 1958 and the family joined him later in India. Baxter was overwhelmed by the poverty and the situation of ethnic minorities. The Indian poor would haunt his imagination and his poetry. His sense of displacement and disorientation is evident in the ‘Asian’ poems of his next collection, Howrah Bridge (1961). Baxter’s later compulsion to leave his family and attempt an alternative lifestyle at Jerusalem must be considered in this context.

Returning to New Zealand wasted by dysentery, he showed increasing disillusionment with New Zealand society. Drama became a vehicle for such criticism. The Wide Open Cage, which was staged in 1959 by Richard Campion, explored themes such as guilt and alienation in relationships. Its success inspired Baxter to write Three Women and the Sea (1961) and The Spots of the Leopard (1962). In 1960 Baxter became embroiled in a controversy over Curnow’s Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse. His argument that Curnow misrepresented the state of New Zealand poetry by under-representing younger poets did little to lessen an antipathy his erstwhile champion had developed towards him.

Becoming a postman in 1963, he wrote The Ballad of the Soap Powder Lock-Out as a light-hearted contribution to the postal workers’ industrial action against delivering heavy soap powder samples. More significant were a number of polemical poems protesting against the Vietnam War. Themes inherited from his pacifist parents, and explored in his unpublished adolescent verse, were reworked to satiric effect in such poems as ‘A Bucket of Blood for a Dollar’ and ‘The Gunner’s Lament’. Poetry Magazine had published A Selection of Poetry in 1964, but Baxter’s next major collection was the widely praised Pig Island Letters (1966).

In 1966–67, Baxter was Burns Fellow at the University of Otago. It was a triumphant homecoming for the man who had left twenty years earlier under a cloud of failure. Baxter took an active part in university life, protesting against Vietnam and satirising the university prohibition against student cohabitation in his pamphlet A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting, Elicited by the Decision of the Otago University Authorities to Forbid this Practice Among Students. Through all this his creative output was staggering: he wrote numerous poems, and published a selection, The Lion Skin: Poems (1967), through the university’s Bibliography Room.

Revisiting the site of his painful but formative adolescence also impelled Baxter to revisit, in his poetry, the themes and locales of the verse of that period. Family memories and Otago landscapes again feature, but always with the presence of death, at times subtly, at other times looming, within the poetic frame. A marked change in style accompanied these variations on earlier themes. Whereas the youthful poetry might, with ponderous metre and latinate diction, move towards a final grand, sonorous phrase, now unrhymed run-on couplets (increasingly the unit of choice in Baxter’s later work) create a tone both direct and personal. Baxter’s later poetry becomes stripped of artifice and abstraction, until all that remains is a personal voice ‘almost ostentatiously matter of fact’ (Vincent O’Sullivan).

In 1967, Baxter also published two volumes of criticism—Aspects of Poetry in New Zealand and The Man on the Horse—and saw a number of his plays and mimes staged by Dunedin director Patric Carey, among them The Band Rotunda, The Sore-Footed Man, The Bureaucrat and The Devil and Mr Mulcahy (see also Theatre). In 1971 Heinemann Educational published two volumes of his plays—The Devil and Mr Mulcahy [and] The Band Rotunda and The Sore-Footed Man [and] The Temptations of Oedipus (the latter performed in 1970). Just as Baxter’s verse supplied several of the characters for these dramas, so his experiences as an alcoholic and working with alcoholics supplied a usefully emblematic ‘tribal’ context within which human frailties were examined through a mythical, or archetypal, lens. The majority of Baxter’s drama is in Howard McNaughton’s edition of his Collected Plays (1982).

In 1968 Dunedin’s Catholic Education Office employed Baxter to prepare catechetical material and teach at Catholic schools, and his articles for the Catholic periodical The Tablet were collected and published in The Flowering Cross (1969). Yet the Fellowship appeared to have drained him of energy and refilled him with doubt. He struggled in his marriage, fearing the trap of domesticity; found difficulty relating to his children; and was dogged by the feeling that words had become impotent and should be replaced by actions. Around April 1968 ‘a minor revelation’ led him to think of Jerusalem (in Maori ‘Hiruharama’)—‘the mission station on the Wanganui river’. He thought he might go to this small Maori settlement, bordered by a Catholic church and a convent, and ‘form the nucleus of a community where the people, both Maori and pakeha, would try to live without money or books, worship God and work on the land’. Following the family’s return to Wellington in December, Baxter left home to put his beliefs into practice.

Auckland was his initial stop. There he failed to hold down the job Hone Tuwhare found for him at the Chelsea sugar refinery. All that came out of the experience was the trenchantly satirical poem Ballad of the Stonegut Sugar Works. He discovered his Auckland niche in a cluster of run-down squats in the suburb of Grafton. Number 7 Boyle Crescent, where he settled in Easter 1969, became a drop-in centre for drug addicts. Baxter, adopting the Maori transliteration of his first name, ‘Hemi’, set about counselling and attempting to establish a Narcotics Anonymous organisation similar to AA. His appearance—barefoot, bearded and shabbily dressed—attracted the attention of both media and police, who suspected his motives and morality. He put the drug users’ side of the story in ‘Ballad of the Junkies and the Fuzz’, and also published a selection of twenty years’ verse in The Rock Woman (1969), but poetry was not his main focus. By August 1969, the Boyle Crescent period had ended and Baxter was heading for Jerusalem, to begin his commune.

He sought there to form a community structured around key ‘spiritual aspects of Maori communal life’, to recover values New Zealand’s Päkehä urban society had lost. He recorded aspects of his philosophy of communality in Jerusalem Sonnets (1970) and Jerusalem Daybook (1971), but in practice the commune lacked order. Baxter could not regulate numbers or behaviour; the media sensationalised his activities; and the locals became increasingly uneasy. Problems compounded because he was often away—in Dunedin visiting his dying father; on speaking tours; and on 8 February 1971 protesting with young Māori radicals at Waitangi.

The commune’s first phase ended in September 1971 and Baxter returned to Wellington, but in February 1972 the Jerusalem land-owners permitted him to return with a smaller, more cohesive, group. His last collection, Autumn Testament (1972), dates from this period.

By August 1972 Baxter was drained, physically and emotionally. He sought refuge on a small commune in Auckland. On 22 October he died of a coronary thrombosis.

A memorable literary and spiritual commemoration ensued. His body was escorted back by his family to Jerusalem where, in a rare honour for a Pākehā, he received a full Māori tangi and was buried on tribal land, attended by hundreds of people from the many walks of life with which Baxter’s intersected. A boulder inscribed ‘HEMI / JAMES KEIR BAXTER / I WHANAU 1926 / I MATE 1972’ marks the grave.

Other monuments included a number of posthumous publications: Futuna Press printed two small selections of religious writing, The Six Faces of Love (1972) and Thoughts About the Holy Spirit (1973); a selection of his last poems appeared in Stonegut Sugar Works, Junkies and the Fuzz, Ode to Auckland, and Other Poems (1972); and the Australian Max Harris paid tribute to Baxter’s bawdy side by publishing Two Obscene Poems (1973). Of more importance were four posthumous collections edited by J.E. Weir: The Labyrinth: Some Uncollected Poems 1944–72 (1974), The Bone Chanter: Unpublished Poems 1945–72 (1976); The Holy Life and Death of Concrete Grady: Various Uncollected and Unpublished Poems (1976); and, most significantly, Collected Poems (1980). Weir has also written The Poetry of James K. Baxter (1970), and edited, with Barbara Lyon, A Preliminary Bibliography of Works by and Works about James K. Baxter (1979).

Frank McKay’s James K. Baxter as Critic (1978) is an edition of selected critical writings, and his Life of James K. Baxter (1990) is the essential biography, although W.H. Oliver’s James K. Baxter: A Portrait (1983) offers an interesting perspective and a lavish selection of illustrations. Baxter’s writing has generated a large amount of critical material, including a complete issue of the Journal of New Zealand Literature (vol. 13, 1995), but little has been written to rival O’Sullivan’s critical monograph James K. Baxter (1976), although Charles Doyle’s James K. Baxter (1976) is more extensive.

O’Sullivan suggests that the real achievement of Baxter’s verse is as ‘the most complete delineation yet of a New Zealand mind. The poetic record of its shaping [being] as original an act as anything we have.’ If, at times, Baxter appears to evaluate New Zealand society harshly, his judgements are always from the perspective of one intimately involved in the social process. His criticisms of national life and his ultimate decision to step out of the mainstream seemed to develop naturally from the preoccupations of a lifetime of verse. Yet these preoccupations were, as a rule, neither negative nor despairing. Rather, the deliberately mythological cast of mind that underpinned his poetry sought to place the individual (and the nation) within a wider frame by directing attention towards universal elements of human experience. The Baxter who, writing shortly before his death, found the Medusa’s head of present-day urban civilisation—with its ‘depersonalisation, centralisation, [and] desacralisation’—intolerable, could still find reason for hope ‘in the hearts of people’.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

The Tree House: James K. Baxter's Poems for Children (2002) is the first illustrated edition of his work for children, in recognition of his death 30 years ago.

O Jerusalem: James K. Baxter an Intimate Memoir (2002) by Mike Minehan offers a poetical and sensitive insight into the author's relationship with Baxter, the son she bore him and the influence these events have had throughout her life.

In 2009, Auckland University Press released James K. Baxter: Poems, a collection of Baxter's work selected and introduced by Sam Hunt.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

• Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

• Mythology of Place - a homage to James K Baxter