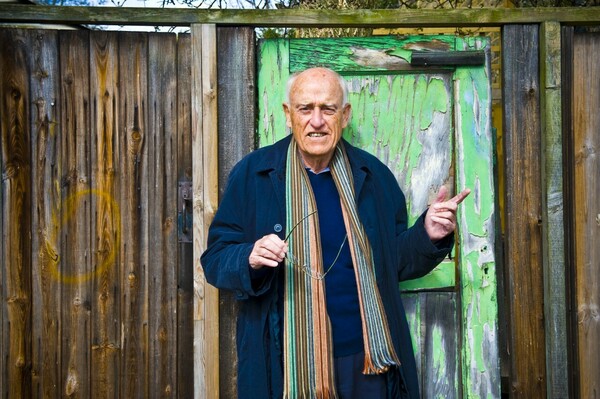

Dan Davin

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Davin, D.M. (Daniel Marcus) (1913–90), was born in Invercargill, fourth of six children of working-class Catholics of Irish (Galway) extraction. His father worked as a labourer, and subsequently guard, on the railways. Dan spent his early childhood in Gore, where he witnessed the flooding of the Mataura River, discovered solitude—in which he taught himself to read—and had his first formative experiences of Catholic school and Sunday church. The family returned to Invercargill, where he attended the Marist Brothers’ School until 1929, then won a scholarship to Sacred Heart College in Auckland. He found himself in a class of clever boys that included Michael Joseph, who became a lifelong friend. Davin excelled and escaped through work from boarding school restrictions that were painful after his free life in Southland. After one year of sixth form he won a national scholarship to Otago University, where he studied history, English, French and Latin.

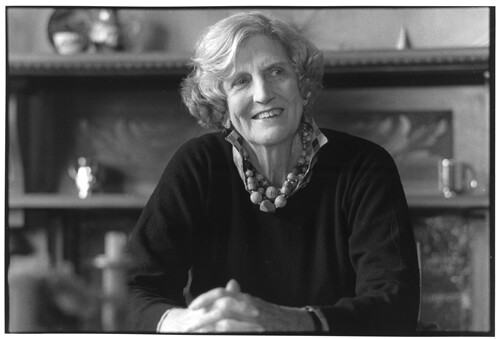

Soon he met Winnie Gonley (later Winifred Davin), four years his senior, already in her MA year in English literature. Under her influence, and with his own strong work habits, Davin immersed himself in literary and linguistic study, reading widely. He adopted a bohemian style, read the 1890s poets of decadence, taught himself German, and devoured the radical fiction of the age: Dostoevsky, George Moore, Proust, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Mansfield and Joyce. His first published work appeared in the student newspaper The Critic and the Otago University Review. He took a first class MA in English (1934), and another in Latin (1935). At his second attempt (his bohemian life having caught him up in scandal the first time) he won a Rhodes Scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford, from 1936, where he read Greats (classics and philosophy). Here he established a close friendship with Gordon Craig, later a renowned scholar of German history, and crystallised his intention to be a writer. He began a novel, provisionally titled ‘The Mills of God’, and wrote short stories, never published. He travelled to Galway, where he was appalled by the poverty, and to Venice. With Winnie, who joined him in 1937, he visited Ireland, Italy, Germany and France. Paris became their preferred city, the bohemian ambience of Montparnasse appealing to Davin’s self-image of the literary outsider. He graduated with first class honours at Oxford in June 1939, and a month later he and Winnie were married.

At the outbreak of war he joined the British infantry, being assigned to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, but after OCTU transferred in July 1940 to the New Zealand Division, at Mytchett, Surrey. He was writing as much as military service allowed, and began to keep a diary. His novel, retitled Cliffs of Fall, was finished and he began another about Parisian bohemian life. He went with the division to Greece in the spring of 1941, saw action on Mount Olympus, and took part in the withdrawal (when he lost his unfinished manuscript) and evacuation to Crete. Here he was appointed 23 Battalion Intelligence Officer. On the first day of the German airborne invasion, he was wounded in the thigh, groin and hand, and after several days of pain and delay, evacuated by sea to Egypt.

After recuperation he was appointed to Military Intelligence, 8th Army HQ, Cairo, where he made friends who were to remain important: Edgar (later Sir Edgar) Williams, later editor of the British Dictionary of National Biography; Geoffrey (later Sir Geoffrey) Cox, eminent New Zealand journalist; Paddy Costello, another brilliant New Zealand linguist of Irish extraction, later a controversial diplomat; and John Willett, after the war a literary journalist with the Times Literary Supplement. Outside the community of intelligence work, Davin enjoyed the cosmopolitan side of wartime Cairo, became friends with poets Bernard Spencer and Terence Tiller, and knew writers as diverse as Lawrence Durrell, Olivia Manning and Richard Hughes. He fell in love with a Dane of German origin, Elizabeth Tylecote, by whom he later had a daughter.

In what spare time he had from work and social life he wrote short stories, mainly about his childhood in New Zealand, his student days in Dunedin and Oxford, and the war in the Middle East. Some were published in John Lehmann’s Penguin New Writing (No. 13) and Life and Letters Today (Vol. 38, No. 72), and became the core of his first collection, The Gorse Blooms Pale (1947). In October 1943 he returned to the desert front and took part in the battle of Alamein and the pursuit of Rommel’s Afrika Corps, in a forward intelligence unit. He later rejoined the ‘Div.’ in Italy as GSO 3 (I) to Lt.-Gen. Freyberg, VC, from February to July 1944, a period that included the battle for Cassino, the advance up the Liri Valley, and the fall of Arezzo. Promoted major, he served the last year of the war in the German Control Commission in London, making friends with bohemian writers such as Julian Maclaren-Ross and Dylan Thomas. Cliffs of Fall (1945) was at last published, and he began work on a war novel.

When the war ended he was invited by Kenneth Sisam (the distinguished New Zealand scholar of medieval literature) to take a job at the Oxford University Press. He spent the rest of his working life (1945–78) there, rising from lowly editor to Academic Publisher. He continued writing, expanding his range to include criticism with An Introduction to English Literature (1947, with John Mulgan) and reviews for the BBC, the fledgling journal Landfall, the Review of English Studies and TLS. His war novel For the Rest of Our Lives (1947), and a novel in which he drew profoundly on his experiences as a boy and young man in Southland, Roads from Home (1949), drew critical attention, and fostered high expectations. His subsequent novels were a disappointment, however, to himself and to critics. The Sullen Bell (1956), No Remittance (1959), Not Here, Not Now (1970) and Brides of Price (1972) nonetheless found an audience in New Zealand. A second volume of short stories, Breathing Spaces (1975), collected pieces from the 1950s–60s, many first published in Landfall.

Most of his disappointment as a writer of fiction may be attributed to three distracting talents: as historian, as publisher, and as friend. As historian, he contributed the volume Crete (1953) to the Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War series, a task that absorbed almost all of his energies outside OUP from 1948 to 1953. It remains a model of the genre. Its success drew him into the world of war histories, where his advice was sought for the rest of his life. As publisher, Davin’s work at OUP was recognised throughout the academic world as peerless, helping hundreds of young and established scholars to meet the demands of scholarly publication. As the Press expanded in the 1960s–70s, his role grew, absorbing the time and energy previously devoted to fiction, while what remained went to his family and friends. His home in Oxford with Winnie and their three daughters, and the thatched cottage that he renovated at Dorchester-on-Thame, were places of hospitality for writers and intellectuals from throughout the world, in particular New Zealand. For thirty years from the early 1950s Davin was recognised in Britain as the informal ambassador of New Zealand letters, and his friendships, connections and in particular reviews in the TLS did much to bring generations of New Zealand writers to a larger public. In private he was generous to his many friends, particularly with guidance to younger writers, and his habitual tables at the Victoria Arms, and subsequently the Gardeners’ Arms in Oxford, were places of warm companionship and witty conversation. The talent for friendship was illustrated in his volume of memoirs, Closing Times (1975), with portraits of Julian Maclaren-Ross, W.R. Rodgers, Louis MacNeice, Enid Starkie, Joyce Cary, Dylan Thomas and Itzik Manger, as well as a revealing introduction. It is widely considered his best book.

In retirement in the 1980s Davin struggled with poor health, in particular depressive illness. He visited New Zealand in 1978, taking part in the Victoria University Seminar on the New Zealand Short Story, in ‘conversation’ with James Bertram. He was often in pain in these last years, but his Selected Stories (1981); Night Attack (ed., 1982); and The Salamander and the Fire: Collected War Stories (1986) show him still thinking about the short story form in interesting ways. His other editions were New Zealand Short Stories (1953, in collaboration with Eric McCormick and Frank Sargeson); Katherine Mansfield: Selected Stories (1953); and English Short Stories of Today (1958), 2nd edn as The Killing Bottle (1988). Bertram’s Dan Davin (1983) contains some biographical material and a critical appreciation. D.H. Akenson, Half the World from Home (1990), argues the case for Davin as historian. The biography is by Keith Ovenden, A Fighting Withdrawal: The Life of Dan Davin, Writer, Soldier, Publisher (1996).