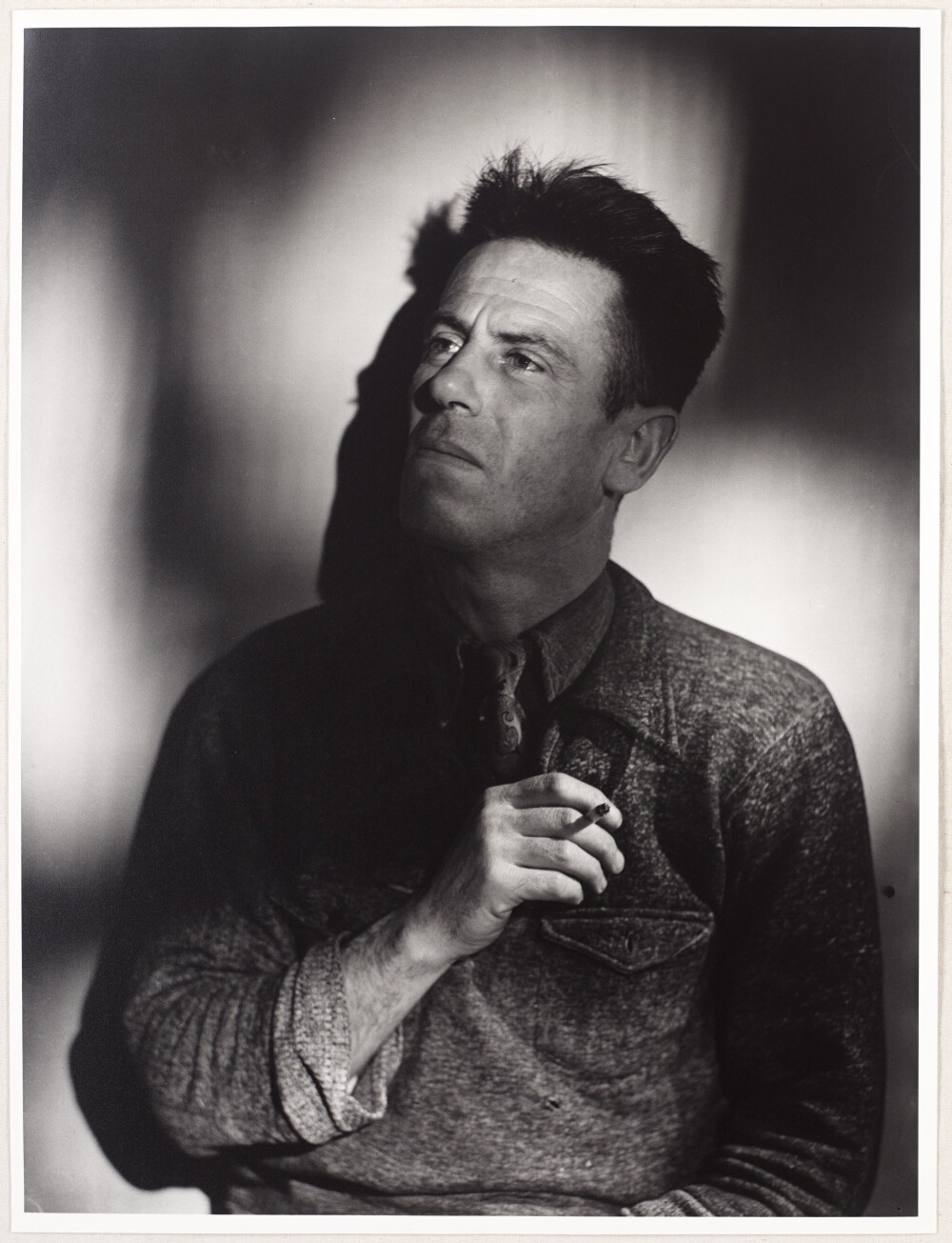

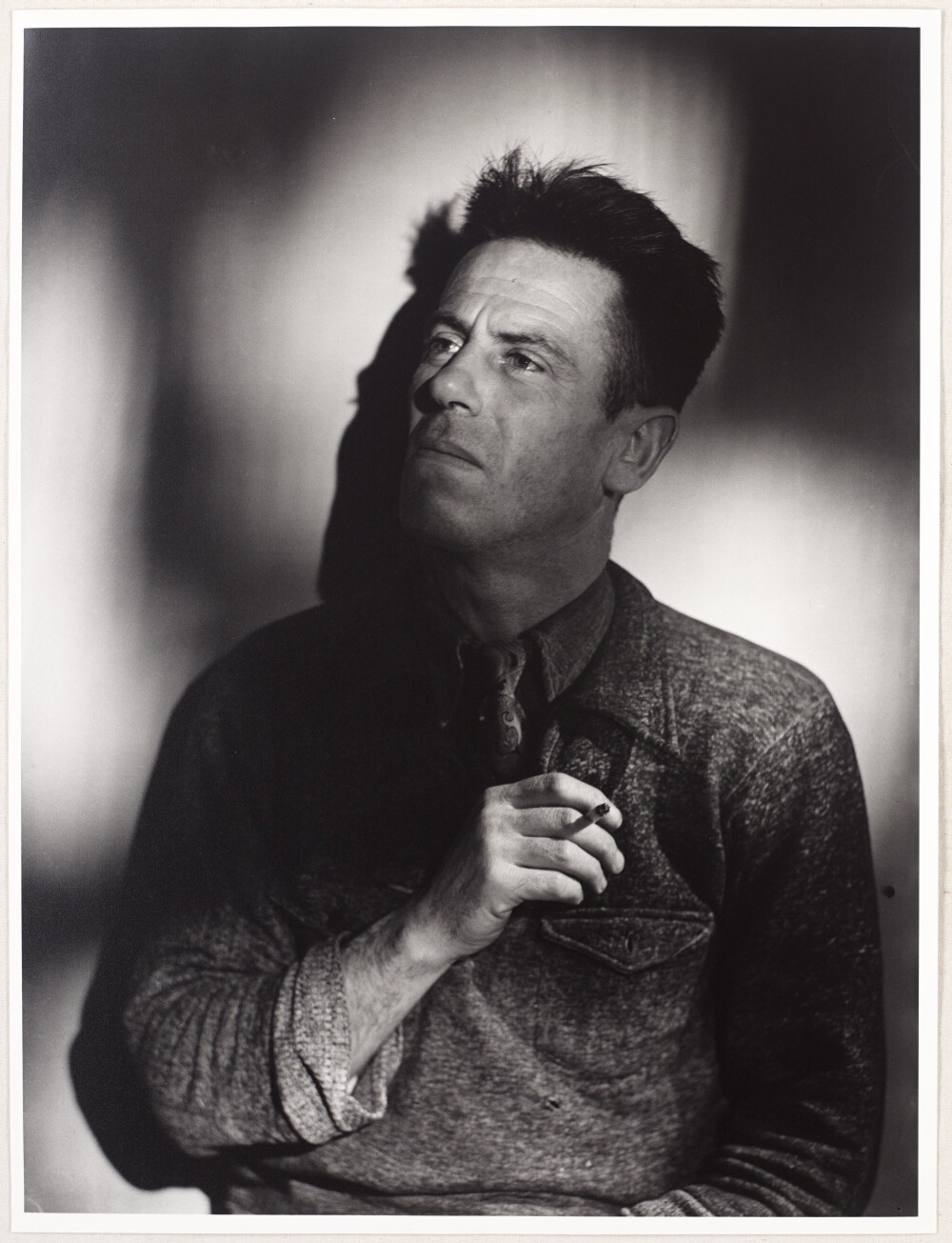

R.A.K Mason

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

R.A.K. Mason was the 1962 Robert Burns Fellow at the University of Otago.

Mason: The Life of R.A.K Mason by Rachel Barrowman (2003), investigates the puzzle of why, after his extraordinaty beginning Mason almost completely stopped writing poetry. Was it because of 'the failure of a gift', to quote C.K. Stead? Later in life, Mason was diagnosed with manic depressive illness. Might this provide a clue to the patterns of behaviour seen throughout his life?

'This wonderful, scrupulous book at last explains the writer who produced New Zealands first great poems - as well as the damaged, courageous man who lost his gift'. Bill Manhire.

Four Short Stories 1931-35, with an afterword by Rachel Barrowman (2003) contains the only four short stories published by R.A.K. Mason (1905-1971), one of New Zealands most important poets. The book was published by The Holloway Press, established to publish a range of texts appropriate to the technology of hand-printing, which have unusual literary, artistic, scholarly and/or historical interest.

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Mason, R.A.K. (1905–71), was New Zealand’s ‘first wholly original, unmistakably gifted poet’ (Allen Curnow).

He was born in Penrose, Auckland, the son of New Zealand–born parents and, on his mother’s Irish Kells side, the grandson of 1840s colonists. After his father’s unexplained death about early 1912, he and his brother were sent to stay with a schoolteacher aunt at Lichfield in the southern Waikato. She taught the boys until the end of 1915, when Mason returned to Auckland for a year’s primary schooling at Panmure.

In 1917 he was enrolled at Auckland GS, where he formed a close association, lasting more than a decade, with the future poet A.R.D. Fairburn, and distinguished himself in English and Latin (his well-known translation of Horace’s ode ‘O Fons Bandusiae’ was apparently done as a class homework exercise). In 1923, because of his poor record in mathematics, Mason was unable to go on to Auckland University College, where he had hoped to continue his classical studies, and instead became a tutor at the private University Coaching College. In his spare time he was pursuing his boyhood interest in writing verse, and in 1923 he produced his first ‘book’ (handwritten, handbound, three copies) of four poems (including three ‘Sonnets of the Ocean’s Base’), titled In the Manner of Men.

His first true publication, however, was The Beggar, printed by Whitcombe & Tombs in an edition of 1000 copies and published by Mason privately in 1924. Although a number of these twenty-two poems have since been anthologised many times (Harold Monro of the Poetry Bookshop in London published two, ‘Latter-day Geography Lesson’ and ‘Body of John’, in No. 39 of his miscellany The Chapbook in 1924, and two others, the sonnets ‘The Spark’s Farewell [to its Clay]’ and ‘Miracle of Life [I]’ in Twentieth Century Poetry in 1929); and although some (those mentioned plus ‘Old Memories of Earth’ and ‘Sonnet of Brotherhood’) have now entered the New Zealand literary canon, the booklet did not sell; so disappointed by the lack of interest locally was the young poet that he is supposed later to have dumped a bundle of 200 copies in the Waitemata Harbour. Despite this failure, in 1925 he had five new poems (including ‘Song of Allegiance’) printed on a folded sheet of card, under the title Penny Broadsheet and dedicated: ‘To (?) the Unknown Hero who sent me £3 in appreciation of "The Beggar" as a Token of Gratitude to himself (and a Hortatory Example to Other People!).’ On the back it announced: ‘If you are anxious to help the cause of young New Zealand Literature, buy / "The Beggar" / A rather remarkable / little book / Price One Shilling / post free—from the Author’.

In 1926 Mason began part-time studies towards a BA in Latin at Auckland University College. For the next three years he wrote little poetry, possibly because of the poor reception of his earlier work combined with his growing interest in radical and student politics. Some poems appeared in the Auckland Sun, which also published a sympathetic evaluation of his work by Ian Donnelly at the end of 1928. By then Mason had determined to adopt a more public position (‘I do want to brighten life and make this world a better place for my being in it’); he wrote later (in Making a Poem, 1959) of his developing feeling that ‘poetry should and could be as it was so long in Scotland and Ireland, a thing of the people but at the same time profound. So the poem has a simple surface appearance but with deeper layers of significance beneath.’ At the same time, ‘I felt strongly the need for poetry and drama to move more closely together with drama benefiting by the bite and precision of poetry, while poetry should learn again the simple and open texture of drama’. One result was the verse play Squire Speaks (published as a play for radio by the Caxton Press in 1938, ten years later), generously described by J.E. Weir in his critical monograph on Mason as ‘a fashionable example of the Marxist popular drama of the period primarily a political, not a literary exercise’.

By 1929 he was writing poetry again and already planning his next collection. Late that year he lost his tutoring job and spent the summer back in the Waikato, working as a farm labourer. An extended diary-letter to his friend Geoffrey de Montalk (by then in London), written during January 1930, was published in 1986 by the Nag’s Head Press, Christchurch, as R.A.K. Mason at Twenty-Five; this offers considerable insight into his creative thinking (he transcribes the original version of what, with little alteration, has become possibly his best-known poem, ‘On the Swag’) at the start of the year that is generally regarded as the most intensive of his writing life. Besides completing a good number of poems, in 1930 he began a ‘partly autobiographical’ novel and wrote uncompromisingly radical articles for the New Zealand Worker and articles condemning New Zealand’s administration of Western Samoa. Between 1931 and 1934 poems from his unpublished manuscripts appeared in the Auckland University annual Kiwi and in the new university-based literary quarterly Phoenix. Mason was asked to take over the editorship of Phoenix from its third issue (March 1933), transforming it in its last issues into ‘an aggressive and polemical instrument’ (Weir), writing out of ‘passionate indignation against social wrong and inequality, and scorn of public stupidities with a vehemence and directness rare in New Zealand during those years of economic crisis and depression’ (Curnow).

Mason’s next collection of poems, No New Thing, was meanwhile being rejected by publishers in Boston and London. Its troubled history was by no means over even after Bob Lowry agreed to design and hand-set the work at his Unicorn Press in Auckland in 1934. The project was ambitious, with a simple, elegant design and hand-woven binding cloth; but because of a dispute with the binders the 100 signed copies intended for public sale were never issued (though some copies were later released privately under the imprint Spearhead Publishers). As Weir comments: ‘The collection was of such excellence—one of the best single collections by a New Zealand poet—that it deserved a kinder fate.’ That kinder fate did await Mason’s work after Denis Glover established the Caxton Press in Christchurch in 1936, for Caxton published nearly all of his poetic output from about 1936 onwards. Their first volume was End of Day (1936): only five poems, including ‘Prelude’ and the call to revolution ‘Youth at the Dance’. To Recent Poems, the 1941 collection of new work also by Curnow, Fairburn and Glover, Mason contributed a group of five love poems, including the lyrical ‘Flow at Full Moon’.

The same year also saw the publication of This Dark Will Lighten: Selected Poems 1923–41. This was the first proper selection of Mason’s poetry and made the best of his early work widely available for the first time. It included three poems from In the Manner of Men and eleven from The Beggar (revised to remove archaisms); the format of all these, and the three from the Penny Broadsheet, was altered to conform with the ‘hanging indent’ style he used for his poems from about 1930. Also included were fifteen of the twenty-five poems in No New Thing, four from End of Day and ‘Flow at Full Moon’, as well as one new poem, another ‘Prelude’, beginning ‘Here are the children / of the best part of a lifetime’. There were to be few more such ‘children’: only one, the denunciatory ‘Sonnet to MacArthur’s Eyes’ of 1950, was subsequently published in the Collected Poems assembled for Glover and the Pegasus Press in 1962 (second edition 1963; new edition 1971; reprinted by Victoria University Press 1990). This gathered together nearly all of Mason’s published poems, including some hitherto uncollected pieces, and a selection of unpublished poems from 1924 to 1930; it had an unabashedly evangelical yet critically acute introduction by Allen Curnow (from which the quotations in this article are taken).

His poetic activity may have virtually ceased by 1941, but Mason had a busy thirty years of life left. He continued to work for left-wing theatre groups in Auckland and to write didactic plays for stage and radio (the dance-drama, China, was published in 1943, and republished as China Dances with other verses in 1962); he became a strong advocate for a national theatre after the war. From 1941 to 1943 he edited a communist newspaper, and from then until 1954 was assistant secretary of the Auckland Builders’ and General Labourers’ Union, for whom he also edited the journal Challenge and under whose auspices he published Frontier Forsaken: An Outline History of the Cook Islands in 1947. Suffering ill health, he then worked as a landscape gardener, but was able to visit China as first president of the New Zealand–China Society in 1957. In 1962 he received the Burns Fellowship at Otago University, where he wrote some new poems (three were published in the Students’ Association Review) and a verse-play, Strait is the Gate (broadcast by the NZBC in 1969). Also in 1962 he married his longtime companion, Dorothea Beyta, and in 1965 they returned to Auckland, where Mason died at Takapuna.

Most critics share Curnow’s view and regard R.A.K. Mason as New Zealand’s first authentic poet, who could unselfconsciously populate the Waikato, the Waitemata, Otahuhu and Papatoetoe with figures from European myth and history such as Chatterton, Gaius Marius, Diana, Herostratus and Aeneas (‘Wayfarers’). Yet his poetic vision was only incidentally local. The earlier poems are preoccupied mainly with the temporariness and yet connection of all human lives, with the ‘individual soul standing grimly’ between past and future and the wider human brotherhood that our predicament must engender. Later poems often dramatise the suffering, as in ‘Judas Iscariot’ or ‘Footnote to John ii 4’ (‘Each one of us must do his work of doom’), making its individuality unique yet universal. These philosophic themes are treated in a distinctive and highly personal way: a combination of defiant desperation, dour stoicism, classical pessimism, dismayed emotion and shocked religious faith, tempered with a rather macabre humour and occasional tenderness.

If philosophically Mason places himself in the grand English tradition of ‘Shakespeare Milton Keats’ and Shelley—‘They are gone and I am here / stoutly bringing up the rear’ (‘Song of Allegiance’)—stylistically he belongs in the line of English poets from Dowson, Hardy and Housman to the Georgians (with echoes of Catullus and Horace). His poetic voice is equally distinctive: despite the archaisms, the forced rhymes, the sometimes overblown or stilted language, there is also an energy, a dramatic urgency expressed with colloquial spareness, a supple ‘muscularity’, which achieves a ‘ruggedly individual voice that, as it puzzles over what to say, transforms even gaucheness into a kind of authenticity’ (MacD.P. Jackson). This ‘peculiar intensity’ is in part a consequence of his extraordinary youth: Mason was only nineteen when he published The Beggar, which so struck Curnow, and over four-fifths of the Collected Poems were written before he turned 25. In one of his journals Mason noted: ‘I do not invent the words; I do not even repeat them from memory. I say them at the bidding of some invisible prompter far back in the dark stage of my mind.’ This confirms the impression defined by C.K.Stead (In the Glass Case) that Mason’s best poems were ‘spontaneous expressions of feelings not always perfectly understood by the mind as it brought them forth’, and that he was ‘a poetic medium rather than a maker of poems’. The ‘increased self-awareness’ evident in No New Thing, even though it contains his finest work, suggests that ‘the qualities distinguishing the earlier work could not be maintained’, and Mason’s poetic silence after about 1940 is compellingly attributed to ‘the failure of a gift for which the will could provide no substitute’.

AM

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2008, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'The Early Poets'