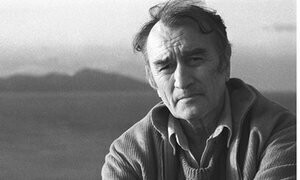

Vincent O'Sullivan

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

O’Sullivan, Vincent (1937– ), born in Auckland, is poet, short story writer, novelist, playwright, critic and editor.

A graduate from the universities of Auckland (1959) and Oxford (1962), he lectured in the English departments of Victoria University of Wellington (1963–66) and (after several months in Greece) the University of Waikato (1968–78), before committing himself to full-time writing.

He served as literary editor of the NZ Listener (1979–80), and then (1981–87) won a series of writer’s residencies and research fellowships in universities in Australia and New Zealand: Victoria (Wellington), Tasmania, Deakin (Geelong), Flinders (South Australia), Western Australia and Queensland. These were interrupted by a year as resident playwright at Downstage Theatre, Wellington (1983). In 1988 he resumed his academic career as professor of English at Victoria University of Wellington.

The winner of many literary prizes, he was the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Fellow in Menton in 1994. In 1997 he also became director of Victoria’s Stout Research Centre.

O’Sullivan’s first book of verse, Our Burning Time (1965), contained poems that had been published in periodicals in New Zealand, UK and USA. An exceptional facility for image-making was already on display. The first of five ‘Poems of Place’ begins: ‘Skopelos drops its village like a pack of cards / from clumsy-fisted mountain, the white sides over.’ The simile may seem contrived, but it catches well the haphazard sprinkling of chalky Mediterranean houses, is picked up in a later ‘shuffled’, and gestures towards themes of chance, fate, and the quirks of history.

Over three decades O’Sullivan’s talent has developed in response to deepening and broadening experience. His verse is collected in Revenants (1969), Bearings (1973), From the Indian Funeral (1976), Butcher & Co. (1977), Brother Jonathan, Brother Kafka (1979), The Rose Ballroom and Other Poems (1982), The Butcher Papers (1982), The Pilate Tapes (1986) and Selected Poems (1992), which draws on all but the first two volumes, and adds new work. Among the strongest of O’Sullivan’s earlier poems are those in which contemporary relationships and states of mind are given a basis in Greek mythology. A traveller, who has visited and lived in diverse parts of the world, O’Sullivan quarries his changing locations for specific reference, while remaining conscious of a contrasting homeland. The sequence of poems From the Indian Funeral, written in reaction to three months spent in Central America in 1975, ends with the poet’s return from the world of the Aztec goddess, with her ‘taloned feet’ and ‘necklace of severed hands’, to ‘green sward and Anchor butter’.

Among O’Sullivan’s most original contributions to New Zealand verse is his creation of ‘Butcher’, affable dealer in flesh and blood and guts, as mouthpiece for a line of racy Kiwi shop-talk that raises perennial poetic concerns. With a cast that includes ‘Sheila’ and ‘Baldy’, the ‘Butcher’ poems exploit a dramatist’s ear for chit-chat, while subsuming the hectoring and reminiscing voices within sheer O’Sullivanese. In Brother Jonathan, Brother Kafka, the awesome certainties of eighteenth-century theologian Jonathan Edwards and the personal, political and metaphysical anxieties of twentieth-century fabulist Franz Kafka represent twin poles between which the poet’s reflections take place, as a visit to New England focuses his thoughts about love and time. These poems, each of four unrhymed quatrains, include some of O’Sullivan’s emotionally most satisfying. The Pilate Tapes imports the colloquial idiom, the dramatic dialogue, and the demotic vigour of the ‘Butcher’ poems into a miniature Passion Play, rendered in a dazzling variety of tones. A far-flung province of the Roman Empire merges into a postcolonial New Zealand peopled with liberal-minded Mr Pilate, Jesus from Hicksville (alias Jix), sly flunky Rat (who ‘doesn’t like Jix, one bit’), Barabbas & Son (‘doing nicely in second-hand / timber’), and that ‘not-bad piece’ Magdalene. The sequence condenses O’Sullivan’s religious and philosophical preoccupations, while being packed with local realities—political, cultural and geographical.

It was only after he had established a solid reputation as a poet that O’Sullivan turned in the 1970s to the writing of short fiction. His stories have been gathered in The Boy, The Bridge, The River (1978), Dandy Edison for Lunch and Other Stories (1981), Survivals (1985), The Snow in Spain: Short Stories (1990) and Palms and Minarets: Selected Stories (1992). They cover a wide range, but are particularly apt to explore various kinds of deprivation, betrayal, rejection, sadness, deceit, estrangement and loss. Death is a recurring theme. Many central characters are on the fringe of a social group, whether struggling to join in, blithely unaware of their position, preferring to remain outside or simply recognising their difference. In ‘The Boy, The Bridge, The River’, the Polish immigrant to New Zealand, Latty, carrying with him his memories of the war, is an alien among marching girls and Lions’ Day, but builds a friendship with his landlady’s ingenuous brother Len. The dwarf narrator of ‘The Snow in Spain’ finds a niche for himself in the sport of dwarf-tossing. The main character in ‘Terminus’, who is teetering on paranoia, says, ‘Forget that masking is natural and even beautiful and set the way we want things to be against the fact of how they are.’ O’Sullivan strips away masks, exposes pretension and self-deception, reveals all sorts of emptiness and loneliness. ‘Testing, Testing ’ finds the Tarzan and Jane within a pseudo-sophisticated marriage. But O’Sullivan’s stories are not reductive: they exhibit a shrewd understanding that pierces to the heart of what it means to be human. O’Sullivan can mock, satirise and laugh, but he also finds dignity in unexpected places. He is interested in the art of living, and in the borderland where truth and lies meet, both in life and in fiction itself. He can move from old folk to children, from rural poverty to metropolitan glitz, from Hamilton to New York. Characters range from retired sugar-works clerk, to company manager, to trendy academics. Technically, his short stories are remarkable for their unsettling shifts of narrative point of view. Their modes span realism and metafiction. Everywhere they are marked by the poet’s eye for detail.

Miracle (1976) is a witty jeu d’esprit, a comic-grotesque satire on national institutions and attitiudes, laced with fable and fantasy. The novel Let the River Stand (1993), which won the Montana New Zealand Book Award for 1994, is O’Sullivan’s major achievement to date. Centred on a Waikato country settlement and covering the period from the end of one World War to the end of the next, it begins, epic-style, in medias res, but only after an italicised page about a woman hospitalised with a head injury, the first of six such passages, one at the conclusion and four serving like entr'acte choruses, as the narrative moves backwards and forwards in time and between groups of characters, whose fates are gradually revealed as interwoven. The everyday life of a typically taciturn rural New Zealand community, with its family feuds and follies, forms the stuff of tragedy and myth. Settings extend to working-class Ponsonby, a Tasmanian apple orchard and Spain during the civil war. There are gestures towards Katherine Mansfield, John Mulgan and other predecessors, with the Depression and the rise of socialism looming in the background. Characters run the gamut from hypochondriac widow to balaclava-disguised prizefighter. The novel has cinematic qualities, both in its visual richness and luminous exactness and in its frequent switches from one centre of consciousness to another. O’Sullivan’s verbal camera lens zooms in and out, tilts and pans; there are cuts and dissolves as the spool unwinds. One section is told through a woman’s diary. A sense of mystery haunts the multifarious elements, until they converge. The climax is an instant, frozen in time. No New Zealand novel has conveyed more completely a sense of history and of those visionary moments that resist its flow.

In the 1980s O’Sullivan the dramatist emerged. He had written radio and television dramas before his first stage play, Shuriken, was performed at Downstage, Wellington, in July 1983. It examines the bizarre situation that led to the death of fifty Japanese soldiers and one New Zealand guard in a World War 2 prison camp at Featherston in 1943. The title is taken from the Japanese word for a throwing-dagger. Japanese prisoners, theoretically committed to a military code of no surrender, and New Zealand guards lacking both experience in their roles and understanding of their charges, are forced into uneasy association, until cultural difference kindles violence. The presence among the ill-assorted New Zealanders of the Maori corporal Tai, who has as much in common with the proud yet subjugated enemy as with his Päkehä mates, creates a significant third dimension, allowing the play to serve as implicit comment on our interracial history. Though the Kiwi soldiers speak the local patois, in structure Shuriken is stylised and non-naturalistic, exploiting the freedoms of the post-Brechtian theatre. In Jones & Jones, about Katherine Mansfield and her close friend Ida Baker, who nicknamed each other ‘Jones’, O’Sullivan again uses such techniques as direct address to the audience, and, taking a hint from Mansfield’s own passion for music hall, punctuates the dialogue with popular songs. The play was commissioned by Downstage for the Katherine Mansfield centenary and first performed in September 1988. It draws on Mansfield’s writings to explore, with considerable wit and verve, an unusual bond, and conjure up the Bloomsbury litterati among whom the two women moved. Animated by Mansfield’s own personality in all its histrionic complexity, it shows, among other things, the emotional tug of the childhood homeland that she had so eagerly escaped. But the relationship between the Joneses is central. Katherine needs her awkward shadow-self in order to scintillate. She bullies, cajoles and mocks Ida —and is fortified by her unconditional love. Specialising in the art of living, she must also learn the art of dying. ‘Jones’, she says, ‘life is nothing if not performance’. Billy, presented at Bats Theatre, Wellington, in August 1989, employs techniques similarly disruptive of naturalism, including tricks with lighting and a litany-like sequence in which characters speak ‘from various points on the stage’. But this is also, in part, a drawing-room drama, with some quite Wildean banter about weighty matters. Set in the New South Wales penal colony of the 1820s, Billy has seven disparate English men and women fret, joke and gossip about their situation, and use the mute Aboriginal servant of the title as a screen on which to project their anxieties and desires. As director Aarne Neeme averred, ‘Boundaries of behaviour are challenged across class distinctions, sexual relations, racial tensions and religious beliefs, as are the notions of authority and civilisation’. Power and its link with violence are among the themes. Here too O’Sullivan returns to his concern with truth and lies. Billy’s dreamlike eruption into speech at the close forms a stunning coup de théâtre. Shuriken (1985), Jones & Jones (1989) and Billy (1990) have all been published by Victoria University Press. Less accessible are ‘Ordinary Nights in Ward 10’ (New Depot, Wellington, March 1984), a dense mix of the farcical, the allegorical and the fantastic, ‘The Lives and Loves of Harry and George’ (Downstage, Wellington, 1994) and ‘Take the Moon Mr Casement’ (Court Theatre, Christchurch, September 1996).

O’Sullivan has, with Margaret Scott, edited five volumes of The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1984– ), as well as Mansfield’s ‘The Aloe’ with ‘Prelude’ (1982), Poems of Katherine Mansfield (1988), and a Selected Letters (1989). His An Anthology of Twentieth-Century New Zealand Poetry (1970, revised 1976 and 1987) was a standard text for a quarter of a century. He is also editor of (among other volumes) New Zealand Short Stories: Third Series (1975), New Zealand Writing Since 1945 (1983, with MacDonald P. Jackson), Collected Poems: Ursula Bethell (1985), The Oxford Book of New Zealand Short Stories (1992), and Intersecting Lines: The Memoirs of Ian Milner (1993). In his critical study, James K. Baxter (1976), he demonstrates the centrality to Baxter’s verse of the seasonal myth at the core of most mythologies. He edited the Wellington current affairs journal Comment during the period 1963–66.

When in Jones & Jones D.H. Lawrence asks Mansfield whether she knows when she is telling the truth, she replies, ‘But I’m an artist Lawrence like yourself. Our vocation is to tell the truth as only the born liar can.’ O’Sullivan’s writing in different genres is unified by his awareness of this paradox.

MPJ

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

O’Sullivan, Vincent (1937 - ) had his first works published as a student in Auckland, with four of his poems selected for inclusion in Landfall in 1960. After completing his M. Litt at Oxford, O’Sullivan began his career as a writer in earnest, publishing his first collection of poetry in 1965. Entitled Our Burning Time (Prometheus Books), this collection garnered O’Sullivan his first literary accolade in the form of the NZSA Jessie Mackay Award, now part of the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

In an editing role, O’Sullivan selected and introduced An Anthology of Twentieth-Century New Zealand Poetry (Oxford University Press, 1970), which is currently in its third edition of publication.

Amidst lecturing at the University of Waikato, O’Sullivan published his first text of many on the subject of Katherine Mansfield and her writing. This initial work, Katherine Mansfield’s New Zealand (Golden Press, 1974), saw O’Sullivan compile various excerpts of Mansfield’s fictional and autobiographical writing in order to speculate her attitude towards her native New Zealand.

In 1978, O’Sullivan ventured into the realm of short story creation, writing The Boy, the Bridge, the River (J. McIndoe), a collection which won the Goodman Fielder Wattie Award, now known as the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, in its year of publication. The following year, his story “The Witness Man” was awarded the now-defunct Katherine Mansfield Short Story Award.

From 1979-80, Vincent O’Sullivan served as literary editor of The Listener.

He returned to Mansfield with The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield (Oxford University Press), co-edited by Margaret Scott. Released as Volume 1 (1984), Volume Two (1987), Volume Three (1993), and Volume 4 (1996), the fifth volume of the collection was released in 2009. The collection was shortlisted for the 2009 Montana New Zealand Book Awards, now known as the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

The Poems of Katherine Mansfield (Oxford University Press, 1988) was O’Sullivan’s next work as editor, and was soon followed by Katherine Mansfield, Selected Letters (Oxford University Press, 1989).

O’Sullivan wrote and released his first full-length work of fiction, Let the River Stand (Penguin), in 1993. Drawing on his childhood knowledge of the Waikato and his experience living and working there as an adult, the novel follows young protagonist Alex, who despite his “nondescript” appearance has a strong inner life. Themes of social disadvantage, passion, and the divided nature resonate throughout the book, speaking to the deep emotional reserves of rural New Zealand. Let the River Stand was awarded the fiction prize in the 1993 Montana New Zealand Book Awards.

O’Sullivan was selected for the 1994 Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship, a prestigious residency allowing the chosen writer to work in Mansfield’s French villa for a period of six months or more.

In 1998, O’Sullivan’s second novel Believers to the Bright Coast (Penguin) was published. A multi-narrator book, Believers to the Bright Coast pits narrator against narrator to debate questions of moral hypocrisy, gathering the divergent characters into a hostage situation in order to comment on the role of society in restraining what Paul Millar terms the ‘grotesque’. Believers to the Bright Coast was runner-up for the Deutz Medal for Fiction, now part of the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Having published poetry at regular intervals since 1965, 1998’s collection Seeing You Asked (Victoria University Press) continued O’Sullivan’s run of critical acclaim, winning the Montana New Zealand Book Award for Poetry.

In 2000, O’Sullivan’s four-decade contribution to literature was recognised when he was made a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

As an essayist, O’Sullivan contributed to the Lloyd Jones-edited Montana Essay Series with his work “On Longing” (2002).

O’Sullivan delved into biography in 2003, writing Long Journey to the Border: A Life of John Mulgan (Penguin). The book was a finalist in the biography category of the 2004 Montana New Zealand Book Awards.

Vincent O’Sullivan was made Professor Emeritus at Victoria University of Wellington in 2004, the same year he was selected for the Creative New Zealand Michael King Writer’s Fellowship.

Nice Morning For It, Adam (Victoria University Press, 2004) won the 2005 Montana New Zealand Book Awards for Poetry. In 2006, Vincent was awarded $60,000 for poetry at the Prime Minister's Awards for Literary Achievement, which recognise writers who have made a significant contribution to New Zealand literature. Then-Prime Minister Helen Clark said of the author’s work, 'Vincent O’Sullivan’s poetry, which is what we are honouring him for tonight, goes to the heart of life’s big themes – love, politics, philosophy, literature and history.'

To celebrate his seventieth birthday in 2007, 28 of O’Sullivan’s colleagues and friends contributed to Still Shines When You Think of It (Victoria University Press), a festschrift edited by Bill Manhire and Peter Whiteford. Blame Vermeer (Victoria University Press), a further poetry collection by O’Sullivan, was also published in this year.

In 2008, the bestowal of an Honourary Doctorate from the University of Auckland marked another significant achievement in O’Sullivan’s literary career.

Further Convictions Pending, the definitive collection of Vincent's celebrated poetry of the last decade, was published by Victoria University Press in 2009.

The poetry collection The Movie May Be Slightly Different (Victoria University Press, 2011) was reviewed by Nicholas Reid in The Listener as a collection which moves through death to positive, concluding that 'these are the poems of a civilised man. An ironist who isn’t sardonic, a romantic who knows romanticism isn’t enough. A treasure house.'

2013 saw the publication of Us, Then (Victoria University Press), a collection of 85 poems of extraordinary “tonal range” as reviewed in The Listener. Us, Then won the 2014 New Zealand Post Book Award for Poetry, now known as The Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

O’Sullivan was named as a 2013 National Library Poet Laureate. Awarded in recognition of outstanding contribution to literature, the award supports the poet in the creation and promotion of their verse for a period of two years.

Since the early 2000s, O’Sullivan has been in collaboration with composer Ross Harris, providing his textual libretto to Harris’ music. This partnership truly fired in 2014, a year in which three of O’Sullivan and Harris’ operas were performed: the war operas Notes from the Front: Songs on Alexander Aitken and Requiem for the Fallen, and the Waihi mine-centred If Blood Be the Price. The Dominion Post reviewed the premiere of Requiem for the Fallen as ‘a model of extraordinary polish and riveting intensity.’

Also in 2014, O’Sullivan’s short story collection The Families was published by Victoria University Press. A 14-story collection, The Families focuses on human interaction and connection. Paula Green for Weekend Herald wrote that the collection shows ‘the songs and blemishes of humanity’.

Being Here: Selected Poems (Victoria University Press, 2015) brings together the best of O’Sullivan’s poems, ranging from verse published in 1973 to works released for the first time in Being Here. The collection was chosen by The Listener as one of the poetry highlights of 2015.

In 2016, O’Sullivan again collaborated with composer Ross Harris to produce a new chamber opera titled Brass Poppies. Portraying the circumstances and effects of Gallipoli both militarily and in domestic New Zealand, O’Sullivan’s libretto received critical praise when it toured New Zealand in March. James Wenley of Metro magazine said of the writing, ‘[i]t’s this mix of poeticism and plain-talking that makes Vincent O’Sullivan’s libretto so brilliant’.

And So It Is (Victoria University Press, 2016), O’Sullivan’s latest poetry collection, comprises 75 new poems from the Poet Laureate. The collection was longlisted for the 2017 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Along with Gerri Kimber and Angela Smith, Vincent O’Sullivan edited The Edinburgh Edition of the Collected Works of Katherine Mansfield: Volumes 1-4 (Edinburgh University Press, 2016), a four part collection of Mansfield’s work.

Vincent O’Sullivan was the Honoured Writer at the 2016 Auckland Writers’ Festival. He passed away in April 2024, with a new collection of ninety poems, Still Is, forthcoming from THWUP.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- ‘Frame’ by Vincent O’Sullivan on Booknotes Unbound

- Interview with Vincent O'Sullivan on Radio New Zealand

- Interview with Vincent O'Sullivan for Cultural Icons

- Article by NZ Poetry Shelf on Poet Laureates

- Article on NZ Poetry Shelf on Vincent O'Sullivan

- Review of The Families on Booksellers

- Review of And So It Is on Booksellers