Sylvia Ashton Warner

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

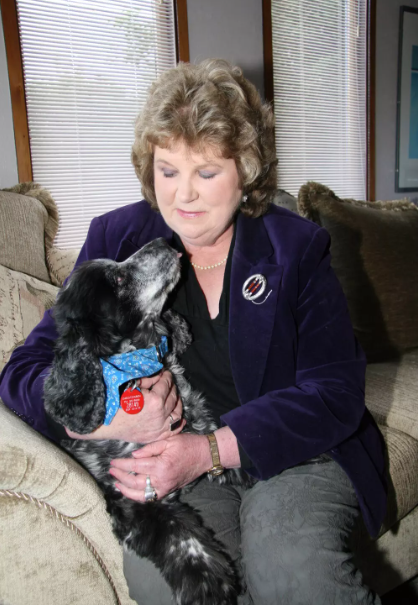

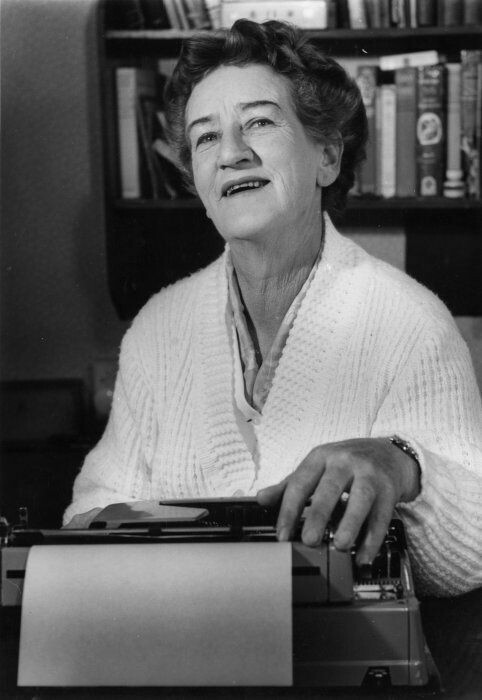

Ashton-Warner, Sylvia (1908–84), was a novelist, autobiographer and educational pioneer. She was born in Stratford, Taranaki, where the family income was earned by her mother Margaret Warner’s teaching in various remote country schools, where she was invariably at odds with the school board and national educational authorities.

Her father, who was crippled with rheumatoid arthritis, told romantic, mythic stories, some of which informed Ashton-Warner’s fiction. Her childhood was marked by extreme material deprivation and interrupted schooling, as her mother moved from school to school, earning barely enough to keep the family of nine children. Without friends, Sylvia depended on her siblings and the natural world to feed her lively imagination. She was educated partly by her forceful mother and partly at various schools, where she invariably felt isolated and disliked.

Having to earn a living, Ashton-Warner became a pupil teacher in Wellington in 1926, and in 1928 she entered Auckland Teachers’ College. Everything in her rebelled against becoming a teacher, because she thought that it would thwart her creativity and her potential success as a concert pianist, artist or writer - all occupations she aspired to.

For her, teaching was synonymous with her mother, whose influence she spent a significant part of her adult life trying to expunge. She married in 1931, and three children were born between 1935–38. Despite her resistance to teaching, Ashton-Warner stayed in the profession from 1938 to 1955, working with her husband in Māori schools in Horoera (East Cape), Pipiriki (Wanganui River) and Fernhill (Hawkes Bay).

For many years, although she was writing and painting while her husband took responsibility for most of the housekeeping and childcare, Ashton-Warner’s public work was centred on her teaching, and in particular, with experiments encouraging Māori children to read.

Her recognition that each person has a ‘key vocabulary’, a set of words with a special meaning relating to their emotional life, enabled her to develop a reading scheme for children who were otherwise failing at school. Though she despaired of being recognised in New Zealand for her contribution to education, she enjoyed a warm response overseas.

After her husband’s death in 1969, she accepted an invitation to assist in setting up an ‘alternative’ school in Colorado. She also lectured at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver. She wrote a number of books about teaching, of which the best known is Teacher (1963).

Ashton-Warner’s teaching and approach to education are closely linked to her contribution to New Zealand literature. The ‘key vocabulary’ not only made the teaching of reading more effective, but also provided insights into the working of children’s minds and released their literary creativity. Unfortunately she was less successful in applying this method to herself, and often depended on alcohol to relieve her inner tension.

Her observation that all people, but particularly children, have an inner and an outer vision, is central to both her teaching and her fiction. The inner world ‘behind my eyes’ and the outer of ‘raw reality’ are often at war with each other, but the tension is also creative. This recognition is one she shares with Janet Frame, who similarly writes about the hidden world ‘two inches behind my eyes’.

Sylvia Ashton-Warner had been writing fiction and publishing short stories for many years before Spinster burst on to the New Zealand and international literary scene in 1958. Ostensibly the story of a single teacher working in a largely Māori school, Spinster is also an account of Anna Vorontosov’s emotional involvement with her pupils, a fellow teacher, the inspector who praises her reading scheme, and the shadowy lover Eugene.

The effort to integrate Anna’s emotional life (the inner world) with her teaching (the world of raw reality) makes this her most popular and successful novel. In 1960 it was made into a film starring Shirley MacLaine, Laurence Harvey and Jack Hawkins, in a studio set that was a Hollywood distortion of New Zealand realities.

In presenting the clash between reality and emotion, Ashton-Warner helped to break the dominance of the realist tradition associated with Frank Sargeson and opened up other ways of interpreting the experience of living in this country. She lamented the poverty of creative vision in New Zealand, and that the experience of many, particularly women, was negated. This also applied to Māori, children and anyone seen as ‘different’ from white males, whose experiences, she thought, had dominated literature since at least the turn of the century.

The test for Ashton-Warner was to create another world, in which the inner and outer could co-exist in creative tension. She explored this possibility in the four novels and collection of short stories written in the 1960s. Spinster had been a novel about a character with ‘no top layer to (her) mind’. Incense to Idols (1960) is its obverse, the story of Germaine de Bauvais, who ‘only live(s) the top half’ of herself, burning incense to the idols of love - men, her appearance and alcohol - rather than to pure emotion itself. While Time magazine listed it, as it had Spinster, among its top ten books of the year, the New Zealand response was both muted and hostile.

In Bell Call (1969) Ashton-Warner achieves the integration of the two worlds in the character of Tarl Prackett, an artist, mother and educational rebel. As the novel’s male narrator observes of Tarl, ‘imagery ignites emotion, which in turn inspires action, and it is action which reaches others’. Ironically, Tarl is no more successful in making contact with others than Anna (in Spinster) or Germaine, but her vision of the world is seen as more coherent and whole than theirs.

Central to this perspective on the world is Tarl’s role as mother to four children, whereas Anna and Germaine were both childless. Ashton-Warner saw mothers as imbued with Madonna-like qualities: ‘Without this beginning point, the love for one’s children or of children in one’s care, a woman seldom comes to universal love.’ The mothering role grounds Tarl as well as giving her access to the world of emotion and creativity, Ashton-Warner drawing on her own experience of child rearing and teaching.

In Three (1970) the mother role is central, as an unnamed writer pays a prolonged and eventually acrimonious visit to her son and his wife. At first glamorising her son’s marriage, the mother finally comes close to wrecking it as she implicitly passes judgement on his wife.

Greenstone (1966) and Stories from the River (1986) demonstrate Ashton-Warner’s affinity with fantasy. The story in Greenstone is loosely based on her own birth family, taking the romantic and legendary - and therefore more palatable - parts and making them into a novel. To the large family, the crippled father with a long heritage, and the mother at war with her employers, Ashton-Warner adds a Māori princess and all the myth and legend she brings with her. Several of the stories in the posthumous short story collection relate to Greenstone in subject matter.

Ashton-Warner also produced two volumes of autobiography. Myself (1966) is an account of the years she and her family spent at Pipiriki on the Wanganui River, though many people are given pseudonyms in view of the intensity of the emotional relationships.

It was her full autobiography, I Passed this Way (1979) that gained her the kind of acclaim accorded only to Spinster among her fiction. It won the New Zealand Book Award for Non-fiction in 1980 and was subsequently made into a film. Though Lynley Hood’s biography, Sylvia! (1988), refutes some of the the author’s account of her life, I Passed This Way remains a fascinating if sometimes fantastic account of the growth of an artist. Its tense ambivalence in relationship to New Zealand seems to be resolved at the end which affirms this land as the one she wants to be part of. Sylvia, a feature film based on her autobiographies, was made by Michael Firth in 1985.

Ashton-Warner’s fear that teaching would render her incapable of making a mark elsewhere was not borne out. Her teaching enriched her fiction, and the creativity from which the fiction came underlay her innovations in education. She broke new ground in New Zealand fiction, opening the world of imagination and emotion as a legitimate subject.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2007, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'Women Prose Writers to World War I' by Emily Dobson