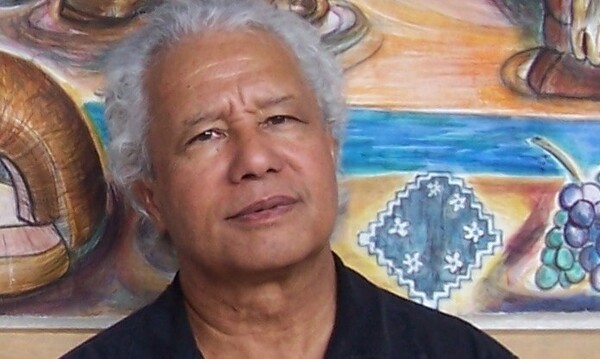

Alistair Te Ariki Campbell

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Campbell, Alistair Te Ariki (1925–2009), poet, playwright and novelist, was born in the Cook Islands and spent his first seven years there. His mother, a Cook Islander, married his father, a third-generation New Zealander from Dunedin, when he withdrew from post-war society, after experiencing the World War 1 trenches, to become an island trader.

The Polynesian and the European strains in Campbell’s personality and work are inseparable. Although his early poetry makes little mention of Polynesia, in its romantic and musical tone and its intense attachment to landscape it is hard not to detect something of those origins, while his later work, more directly Polynesian, nonetheless has the form and tone provided by an education in English and classical poetry.

Although the poet lost his parents at an early age, their personalities and romantic attachment pervade his writing. His father was said to have a good command of various Island dialects and to have been consulted on them by Sir Peter Buck. As a successful trader he achieved considerable social status in Rarotonga.

Campbell’s mother, Teu, revealed in photographs as a shy beauty, was remembered for her kindness and Christian piety. Her father, the Bosini mentioned in his grandson’s poems, was said to know the Bible by heart. The term ‘Te Ariki’ which the poet now uses in his name points to the chiefly origins of Bosini’s family. Campbell later admitted that he knew his mother too little, and much of the melancholy in his personality and poetry is due to that. His father had seemed even more remote, leaving the women, family and servants to raise the children. Campbell’s recorded memories of these first seven years are of South Sea warmth and a certain inner darkness, poetically personified as ‘The Dark Lord of Savaiki’. As Peter Smart wrote: ‘His memories included nightmares as well as dreams.’

Teu died of tuberculosis in 1932, aged 28, and Jock Campbell rapidly became addicted to alcohol. He died within a year. In interviews, Campbell confessed that the next years were a blank in his memory, a grief he had repressed. Much of his later work can be interpreted as an effort to fill that gap, although there are many less personal echoes as well.

In the New Zealand Railways Magazine of 1 July 1933 there is a photograph of two small boys in big hats and coats, with luggage labels attached to their lapels. The taller is Alistair Campbell and the smaller his brother Bill, sent virtually as human packages from the Cook Islands to join a brother and sister in New Zealand. The next years were spent in Dunedin, the South Seas idyll replaced with an orphanage in a provincial town close to Antarctic seas.

Socially too, the boy’s status had changed, from a loved member of a respected family to a child in an orphanage in the years of the Great Depression. The sense of abandonment must have been increased by the fact that he spoke little English, Penrhyn Māori being his native language. Rather than breaking him, this situation made him determined to succeed in this new competitive world. Within a few years he was top of his class and successful at sports (he represented Otago in soccer). Nonetheless he remained a ‘loner’ at school, and found a warm refuge only in the home of friends in the Cromwell Gorge, Central Otago. His first important poems reflect that landscape: ‘This is the kiln / That fired my shaping mind.’ In 1943 he moved on to Otago University, but the strain of competitive living told, and after a minor breakdown he suddenly moved to Wellington.

After initial difficulties he obtained a room at Weir House and was accepted as a student at Wellington Teachers’ College. Considering his later major contributions to educational publishing, it is ironic that he failed to complete his College studies. He was distracted, he has said, by ‘personal doubts and fears’, but also by women and poetry. He helped to edit Spike and found Hilltop and Arachne, publishing verse in all of them. Writing became his way of life, rather than an ‘interest’. With his young friend, Roy Dickson, he travelled to familiar places in Otago and explored new ones such as the Hollyford Valley. In 1947, on another expedition, Dickson was killed, and this tragedy gave rise to the greatest of Campbell’s early poems, ‘Elegy’, published in Mine Eyes Dazzle (1950). It reflected the darkness that was to characterise much of his poetry, and, typically, projected it onto the landscape. At the same time Campbell was developing another theme that was to accompany him throughout his life: the beauty of inaccessible women. Many of the later attempts to order his poems into a coherent whole were to be introduced by ‘Green’, just such a poem written at this time.

In these early poems Campbell largely ignored his Polynesian background and wrote and argued as an inheritor of the European tradition: he was studying Latin and the history and culture of Greece, while the poet he most admired was W.B. Yeats. Together with James K. Baxter, Louis Johnson, Peter Bland and others, Campbell was a member of the (informal) Wellington Group, who felt that the Auckland poets around Allen Curnow were trying to stifle originality by focusing on ‘the New Zealand thing’. This was not a question of subject matter — all of the Wellington poets wrote of local subjects — but of literary orientation. Awareness of international developments seemed essential to the Wellington Group.

After various casual jobs, Campbell found employment as a gardener in the grounds of a Red Cross hospital, an ideal combination of outdoor work and opportunity to write and read when the weather turned sour. Many of his finest early poems were written in the gardener’s hut. He continued to haunt Central Otago whenever possible and on one occasion was followed there by a Wellington student named Fleur Adcock. They courted and wed. Campbell returned to the Teachers’ College and was more successful this time, partly because of the support of friends among students and staff, some of whom were also poets: Anton Vogt, Barry Mitcalfe, Baxter and Johnson. Douglas Lilburn, John M. Thomson and Erik Schwimmer were also among the friends of that time. Literary conversations were intense, but Campbell was not especially productive in the 1950s. It seems that he was preparing for a later phase, and periods of silence have been typical of his career. Nonetheless the hard monosyllables of ‘Aunt Lucrezia’ (1954), the vision of a walking skeleton — the past recovering life — in ‘Bones’ (1956) and the mystery of death in ‘Bitter Harvest’ (1957) suggest, at least with hindsight, that the new themes of (Polynesian) childhood and death and a new harshness in style were being prepared. There is also sufficient evidence that he read widely and with passion in local and international poetry.

Having acquired his degree, Campbell worked as an editor for School Publications and wrote a novel for children, The Happy Summer (1961). He also edited the first Poetry programme on radio (1958). In his personal life great changes were occurring. Fleur bore two sons but his attention turned to Meg Andersen (see Meg Campbell), a beautiful young actor. Campbell divorced and remarried in 1958. Nonetheless, beneath the surface, there were tensions, and in Meg post-natal depression merged into a deep and prolonged nervous breakdown. Campbell suffered stress of his own and in 1960 he, too, suffered some kind of breakdown. For many years he had been subject to nightmares and depression — found partly in his poetry but more explicitly in his plays and later fiction — and in exorcising his devils he turned to memories of childhood. All of this is now more than a personal matter, since it has coloured his writing thematically and emotionally ever since. The poet even found something of value in his attendance at a mental hospital. In an interview with Sam Hunt in 1969 he said: ‘It was almost as if the springs of creativity had become iced over … my nervous breakdown cracked the ice and allowed the spring to flow once more.’

Perhaps the most important component of his therapy and of his poetic development was his acceptance of his Polynesian background. For years, in covering the wounds of childhood, he behaved like a ‘European’ poet; but now he thought and wrote of the Polynesian strain. In the first major instance, Sanctuary of Spirits (1963), he chose to write of the Māori history which surrounded his home at Pukerua Bay, near Wellington. A year later this sequence opened Wild Honey (1964), a collection published in Britain. The protagonist of the radio play The Homecoming (1964) is a Māori writer who resents his outsider status. The awakening of the Polynesian strain in his work was not all therapeutic joy: in 1965 he said, ‘I am of mixed race. The years of solitude get you down. You are different. You are without a tribe.’ He identified with the Ngāti Toa tribe of the area of his current home, but later he was to return to his original home, the Cook Islands, and find a new sense of identity there.

The Homecoming was the first of six plays for radio, a form peculiarly suited to a poet whose words resonate so musically. The best-known of the plays is When the Bough Breaks (1970), of which a stage version was produced and published in Howard McNaughton’s Contemporary New Zealand Plays (1974). It is an expressionistic exploration of a stressed mind. Similarly The Suicide (1966) presents schizophrenia by letting an actor play each part of the personality.

Sanctuary of Spirits was also first conceived as a radio play.

The struggle to define the best version of the poetic vision originally conceived much earlier continued into the 1970s. In 1971 these poems were collected with new ones as Kapiti. This book sold remarkably well and constituted a statement of where Campbell had come from and where he had arrived. The early love and nature lyrics, again revised, were accompanied by poems of social awareness. Dreams, Yellow Lions (1975) was a more mixed collection, suggesting that the poet was experimenting with themes and forms. Personally, too, Campbell moved out to face the social world, taking part in TV documentaries on Kāpiti Island and on his own life and poetry. In 1979 he took part in the ‘Four Poets’ tour of New Zealand with Hunt, Hone Tuwhare and Jan Kemp. He tutored creative writing nationally and internationally and was president of PEN for a year.

Of special significance was his return to Rarotonga in 1976, a return to the experiences of his own childhood. Together with his brother Bill, who had also been in the photo with the railways baggage labels, he travelled to Tongareva (Penrhyn), his earliest home.

The collection The Dark Lord of Savaiki (1980) showed that the poetic experiments and new life experiences had had a profound effect. These were poems of a different kind, with a different voice and a different subject matter: poems of celebration and of love for the Polynesian ancestors. They called for another reassessment, which took place in Collected Poems (1981), where the earlier verse was printed in definitive versions and The Dark Lord of Savaiki, together with some similar poems, was added. The new strain was developed into something even more relaxed in manner in Soul Traps (1985), published at the author’s Te Kotare Press.

Work in various genres deepened this ‘Polynesian strain’. The autobiographical Island to Island (1984), a narrative search for origin, was followed by a mythic-comic trilogy of novels: The Frigate Bird (1989), which was regional finalist for the Commonwealth Writers Prize, Sidewinder (1991) and Tia (1993). At the same time, Stone Rain: The Polynesian Strain (1992) consolidated and highlighted these elements and concerns in the poetry.

In 1996 the Wai-te-ata Press published a finely printed and exquisitely bound version of a new poem, ‘Death and the Tagua’, filled with intimations of mortality, a dream of a ship carrying persons familiar to readers of Campbell’s poems towards some realm of death. It makes a sombre-ironic conclusion to Pocket Collected Poems, also published in 1996, the most recent attempt to present the complete poetic persona, introduced with a major essay by Roger Robinson. It seems designed as a farewell, but it is accompanied by several new poems, and others that have been difficult of access, and the work of shaping a now large oeuvre into a coherent whole seems to be ongoing. Despite the hint of death, Campbell’s readers are hoping that the work will be extended even further and that this dream-filled craftsman will continue to delight them. NW

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Alistair Campbell: Collected Poems won the New Zealand Book Award for Poetry at the 1982 New Zealand Book Awards. In 1992, he was the Victoria University Writers' Fellow.

In 1997, Alistair Te Ariki Campbell was awarded the the Pacific Islands Artist's Award. In 1999, he received an Honorary DLitt from Victoria University of Wellington.

Fantasy With Witches, an enchanting novel set on a fictional, magical Pacific Island, was published in 1999. The story is a blend of reality and fantasy, in which the cultures of the Pacific Islands and their mythologies are woven together with witches and mystical offshore islands that may or may not be a part of the imagination. It follows the adventures of Kimi, together with an eclectic group of characters who make up the population of their island.

Gallipoli and Other Poems (1999) comprises two poetic sequences dealing with the themes of war, peace and love. Campbell writes of his father, among others, who fought in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign.

'Campbell's oeuvre is vital, and varied in subject, voice and structure...' writes John O'Connor in New Zealand Books. "[I]t is essentially original, finely crafted and spans the objective world of sensation and the inner world of spirit or presence.'

Alistair Campbell received a grant from Creative New Zealand in 2000 to write a poetic sequence about his brother, who was killed in Italy fighting with the Maori Battalion in 1945. Published by Wai-te-ata Press, Maori Battalion: A Poetic Sequence (2001) is a sequence of 72 poems that takes the reader into the minds of the soldiers in the Maori Battalion.

Nelson Wattie, who is writing an authorised biography of Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, accompanied him to Italy to visit the battlefields where the Maori Battalion fought, and where Campbell's brother was killed.

Poets in Our Youth (2002) comprises four letters in verse to John Mansfield Thomson, Harry Orsman, Pat Wilson and James K Baxter. Campbell reflects on his years at university when he began writing poetry seriously, and reminisces on the lasting friendships he made at Weir House, a student hostel, and later as a member of the Wellington Group of writers.

In 2005 Campbell published The Dark Lord of Savaiki: Collected Poems, containing the best of his early and middle period poems, as well as his latest collections, Gallipoli and Other Poems, and Poets in Our Youth.

In 2005, he received a $60,000 Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry. That same year, he was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM).

Campbell's 2007 collection, Just Poetry, includes a moving account of a happy childhood in the Cook Islands, as well as recent reflections on Rarotonga and powerful poem on Parihaka. Comic and witty poems range alongside the kind of eloquent lyric for which he is noted.

It's Love Isn't It (HeadworX), a joint collection of love poems by Alistair Te Ariki Campbell and his late wife, poet Meg Campbell, was published in 2008.

Alistair Te Ariki Campbell passed away after a short illness in August 2009.

LINKS

- Alistair Te Ariki Campbell's page on the HeadworX website

- Alistair Te Ariki Campbell's page at the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre's online archive