Owen Marshall

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Marshall, Owen (Owen Marshall Jones) (1941 – ), short story writer and novelist, was born in the North Island town of Te Kuiti. The third son of a Methodist minister, he grew up in an environment in which his father read aloud to his family, scholarship was revered, and the value of books unquestioned. His mother—whose maiden name was Marshall—died when he was two and a half years old. His father remarried when Marshall was 5, and there were six more children. His childhood, a happy time lived mainly in provincial South Island towns, would provide background for a number of stories. After a boyhood spent in Blenheim—‘Seven years of summer days, tar bubbling on the streets’—the family moved, when he was 12, southwards to the town of Timaru, on South Canterbury’s east coast. In this region of South Canterbury and North Otago Marshall has spent his adult years, and the affinity he feels with its people and landscapes is evident in much of his writing.

From five years as a student at Timaru BHS, Marshall went on to study for four years at the University of Canterbury—a period punctuated by two intervals of National Service in the military—before graduating MA (Hons) in 1964.

He received his Diploma in Teaching in 1965 and went into employment, firstly at Oamaru’s renowned Waitaki Boys’ High School where he rose to deputy rector before resigning, after some twenty-five years as a teacher, to write full-time.

Marshall, a voracious reader as a student, admired writers as diverse as Austen, Faulkner, Hemingway, Huxley, Chekhov and A.E. Coppard. To this list he later added great short story practitioners like Joyce, Babel, Pritchett and Sherwood Anderson. However, he consistently rated two lesser-known writers, H.E. Bates and Theodore Powys, among his most important influences: ‘Their writing’, he stated, ‘shares two elements that particularly attracted me: firstly a marked felicity of language, secondly a persistent affection for the countryside and rural people.’

As a young teacher in his mid-twenties Marshall directed his powerful urge to write into two novels, neither of which found a publisher, but one of which he later ‘cannibalised—[with] a certain perverse satisfaction’ to fill in the background of many stories. Still unpublished in his early thirties Marshall decided to concentrate on short fiction, a form that interested him as a reader and continued to interest him as a writer because of its ‘constraints—possibilities [and] challenges’. Changing genres did not lead to immediate publication, but Marshall looked back on the period as a necessary apprenticeship.

Success came in 1977 when the NZ Listener published ‘Descent from the Flugelhorn’—a story set in rural Otago about a rugby player’s encounter with a dying old man. It was against Marshall’s nature to announce himself as an author—‘I have always valued the fulfilment of being a writer, rather than that of being seen a writer’—so using his Christian names as a pseudonym ensured some anonymity. More periodical publications followed, but there seemed little prospect of a book. Finally Marshall gambled on the quality of his writing and paid to publish his first collection, Supper Waltz Wilson and Other New Zealand Stories (1979). The return was handsome: New Zealand’s master of the short story, Frank Sargeson, in his last review, confessed himself unprepared for the book’s powerful impact and passed his mantle to Marshall with the assessment that it was ‘As fine a book of stories as this country is likely to see. And because of [its] density, one that will stand close re-reading for many years to come’ (Islands 30, 1980).

Marshall admired Sargeson, and once said of ‘Conversation with My Uncle’ that ‘I have read whole novels that have less to say, and say it less well’ (NZ Listener, 17 Sep. 1988), but it is also clear that Sargeson exerted no stylistic influence on the younger man. Lawrence Jones, in his essay ‘Owen Marshall and the Sargeson Tradition’ from Barbed Wire and Mirrors, argues that the similarities in their fiction come, in practice, ‘from the experience of a common New Zealand provincial environment’.

Following his debut, collections of Marshall’s stories appeared regularly, but now reviewers were almost universally enthusiastic, and he never paid for another publication. The Master of Big Jingles and Other Stories (1982) was followed by The Day Hemingway Died and Other Stories (1984); The Lynx Hunter and Other Stories (1987); The Divided World: Selected Stories (1989)—a mix of new and previously published material; Tomorrow We Save the Orphans (1992); The Ace of Diamonds Gang and Other Stories (1993); Coming Home in the Dark (1995); and, most recently, The Best of Owen Marshall’s Short Stories (1997), which collects sixty-seven stories from some one hundred and fifty published.

Marshall is too versatile, too adept at adjusting his narrative technique, ever to be described as a formulaic writer, but the body of his work does reveal certain themes, characters and settings recurring. For example, the unlovely Ransumeen family, and the fictional town of Te Tarehi—the focal point of a predominantly Pakeha rural community—weave threads of consistency through segments of his work. Marriages, families and small-town life are often the focus, as is the relationship between the individual and those exclusive male preserves—societies of schoolboys, rugby players, farmers or war veterans— that dominate and confer identity in provincial New Zealand. And at the centre of many of these stories is a solid moral core of esteem for individual integrity.

Against this backdrop Marshall frequently fastens on the outsiders—the loners and misfits, underdogs and losers—who fail to conform. Some characters make grand gestures they alone understand, others live ‘lives of quiet desperation’, still others—the unlikeable and unredeemable—are caricatures, products of the writer’s ‘corrosive eye’. It may be, as Marshall says, that ‘you can get a lot of emotional mileage’ from such characters, yet the way he uses them is often so idiosyncratic that what he illuminates confounds both expectation and preconception. It is Marshall exposing what he calls ‘the fallibility of the real’, revealing the ‘things of great horror and ineffable joy’ that shimmer beneath the objective world.

Marshall’s empathic identification with small-town New Zealand is tempered by a penetrating realism. Lydia Wevers describes the story ‘Mumsie and Zip’ as ‘the blackest and most brilliantly sinister portrait of the suburban marriage in New Zealand fiction’ (New Zealand Books, Dec. 1995). And Vincent O’Sullivan notes how ‘A Southland Girl’ only succeeds when a missing context —‘one defining word [that] has been held over’—is supplied (‘The Naming of Parts: Owen Marshall and the Short Story’, Sport 3, 1989). When the girl’s lover is abruptly revealed as Maori, the narrative reassessment demanded exposes her protective parents as racists.

Marshall is acutely aware that his early stories have a male emphasis that tends to portray women as aggressive, self-righteous and hypocritical. It has, he explains, much to do with his experience as a heterosexual New Zealand male who was a pupil, and later teacher, at a single-sex boys’ school; who spent time in the army—where ‘I was confronted with the antithesis of individual integrity and the values of group loyalty and support’; and who played ‘a good deal of sport largely with young men of my own age’. Time, marriage and the birth of two daughters have tempered this, and recent depictions of women elicit a broader spectrum of responses and evidence a wider range of narratorial sympathies.

Often labelled a realist writer, Marshall prefers to think of himself as an impressionist, and experimentation with narrative technique is a hallmark of his writing. In ‘Choctaw Princess’ his stated intention is to use the ‘rhythm, cadence and hypnotic quality of words’ to produce a ‘language mosaic creating pattern and mood’. In contrast, the narrator of ‘The Lynx Hunter’, who is walking to work, sets up in free indirect discourse a series of surreal self-representations, projecting himself onto his external environment, then interrogating and evaluating the self he sees reflected back.

Many critics rank Marshall among the finest, if not the finest, of New Zealand’s short story writers. O’Sullivan defines the terms of reference by which such an assessment is possible when he argues that Marshall ‘constantly tests and breaks expectation [and] drives the form and its possibilities further perhaps than any other New Zealander apart from the three it is necessary to think of if one wants to place him correctly. With Sargeson, Duggan, Frame.’

Marshall’s stories have been anthologised internationally and he has received numerous honours, including the Canterbury University writing fellowship, 1981; the PEN Lillian Ida Smith Award for fiction, 1986 and 1988; the Evening Standard short story prize, 1987; the American Express short story award, 1987; two second places for the Katherine Mansfield BNZ Short Story Award; the 1988 Scholarship in Letters, as well as an achievement award in 1990; the 1992 Otago University Burns Fellowship; and the 1996 Katherine Mansfield Memorial Fellowship in Menton, France.

The award of the Burns Fellowship enabled Marshall to write his first published novel, A Many Coated Man (1995), which was shortlisted for the 1995 Montana Book Awards. The novel, set in twenty-first century New Zealand, begins with Christchurch dentist Aldous Slaven—out house-painting precariously close to live power lines—narrowly escaping electrocution. While recuperating from burns Slaven discovers that his near-death experience has gifted him with powers of oratory so compelling that he can spellbind crowds for hours, although afterwards he has no recollection of what he has said. In the dry world of New Zealand politics such ability to pull crowds and sway the masses by articulating simple truths is threatening, and his enemies attempt to silence him by incarcerating him in a ‘hospital’. Slaven escapes, however, re-establishes himself as the head of his Coalition for Citizen Power, and resumes his mission to put a sense of moral community back into politics.

A Many Coated Man is not realist fiction; rather, a subtle current of magic realism charges the narrative: characters die only to reappear later; a short doctor becomes tall and elegant; an enigmatic bald-headed man frequently appears, helping but never speaking; and of course there is Slaven’s own startling transformation. But Marshall’s underlying moral is a realist one of world-weary cynicism. The insidious political process triumphs as Slaven begins making the kinds of compromises all too familiar in recent New Zealand politics—negotiating potential coalitions with mainstream parties in return for concessions on his ideals.

Andrew Mason summed up the critical response to A Many Coated Man when he observed that most ‘reviewers, while admiring the lyrical character of the writing, have found the book flawed in technique and puzzling, even obscure, in its direction. Measured against Marshall’s short stories the novel was judged a disappointment—interesting, yes, but a failure’ (Landfall 190, 1995). Given such responses, it seems unlikely that novels will supplant short stories as Marshall’s most acclaimed genre. As Mason concludes, ‘with Marshall less is more.’

Since leaving teaching to pursue his writing, Marshall has run a fiction writing course at Timaru’s Aoraki Polytechnic and edited three books: Burning Boats: Seventeen New Zealand Short Stories (1994), Letter From Heaven: Sixteen New Zealand Poets (1995), and Beethoven’s Ears: Eighteen New Zealand Short Stories (1996). He collaborated with poet Brian Turner and painter Grahame Sydney on Timeless Land (1995), a volume reflecting the three men’s passion for the Central Otago region, and he has written a radio play commissioned by Radio New Zealand. Marshall has been interviewed twice: by Lawrence Jones for Landfall (150, 1984) and by Patrick Evans for In The Same Room: Conversations with New Zealand Writers (1992). A brief autobiographical essay, ‘Tunes For Bears To Dance To’, in Sport 3 (1989), recalls his beginnings as a writer.

Book Council note on the Companion entry:

Owen Marshall spent 20 years teaching at Waitaki Boys' High School, not 25 years as the Oxford Companion suggests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Owen Marshall has twice received the Lilian Ida Smith Award, in 1986 and 1988. He was the Robert Burns Fellow at the University of Otago in Dunedin in 1992.

Marshall was also the 1996 recipient of the Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellowship. One of New Zealand's most long-standing and prestigious literary awards, the fellowship is offered annually to enable a New Zealand writer to work in Menton, France.

He received an ONZM for services to literature in the 2000 New Year's Honours list. In the same year, he received the Deutz Medal for Fiction at the Montana New Zealand Book Awards (now known as the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards) for his novel Harlequin Rex (1999), which went on to be translated and published overseas.

'Y2K is past, the computer and the fridge are still working, but in Owen Marshall's new novel Harlequin Rex the millennium has unexpectedly tossed up another problem, an epedemic called Harlequin which is working its way around the world early in the new century and is particularly effective, for some reason, in New Zealand... There was always an epidemic in Marshall's fictive world, in other words, a neurological disorder called the human condition...' writes Patrick Evans in New Zealand Books.

Marshall was editor of two anthologies of short fiction published in 2001. Spinning a Line collects New Zealand writing on fishing and includes contributions from Keri Hulme, Brian Turner, Patricia Grace and Kevin Ireland. In Author's Choice, New Zealand writers choose a favorite among their own short stories, and comment briefly on their choice. The contributors are Barbara Anderson, Norman Bilbrough, Linda Burgess, Catherine Chidgey, John Cranna, Fiona Farrell, Patricia Grace, Russell Haley, Witi Ihimaera, Christine Johnston, Fiona Kidman, Shonagh Koea, Owen Marshall, Vincent O'Sullivan, Sarah Quigley, Emily Perkins, C.K. Stead, Apirana Taylor, Peter Wells and Albert Wendt.

When Gravity Snaps, a collection of 24 of Marshall's short stories, was published in 2002 and was runner-up for the 2003 Deutz Medal for Fiction in the NZ Book Awards. Gordon McLauchlan writes in the Weekend Herald 'Owen Marshall has the gift of telling stories that take hold of you in a personal way and bring echoes of people, places and events you have known, but not paid enough attention to at the time. It is a magical heightening of the ordinary.'

In 2002, Marshall was awarded an honorary Litt.D. by the University of Canterbury. He was also editor of Essential New Zealand Short Stories, published that year.

In 2003, he became the inaugural recipient of the $100,000 Michael King Writers' Fellowship.

A poetry collection, Occasional: Fifty Poems was published by Hazard Press in 2004. David Eggleton writes in the NZ Listener: 'The much-decorated fiction writer’s first collection of poems, entitled Occasional, is unmistakably elegiac in tone: poetic salutes to events drawn from the relentless flux of time . . . Sounding at times like a fount of received wisdom, Marshall weighs his words as if regarding you with a raised ironic eyebrow. The poems employ the same bluff, resilient, yet harmonious language as Marshall’s prose.'

In 2005, Marshall was appointed an adjunct professor by the University of Canterbury.

His 2005 short story collection, Watch of Gryphons and Other Stories (Vintage), employs a rich variety of setting and subject: the empty tussock dryness of New Zealand's South Island, the ancient stone buildings of Italy's Perugia, unsolved murder, the capricious indignity of Alzheimers disease, adoption. Several longer stories give Watch of Gryphons a special depth and resonance, but present, as always, is the startling range and subtlety of emotion that readers have come to expect. Watch of Gryphons was nominated in the 2006 shortlist for the NZ Book Awards.

Marshall's third novel, Drybread, was published in 2007 (Vintage). 'Drybread’s success lies in Marshall’s dextrous examination of the ambiguities of relationships – between parents and children, spouses, work colleagues and lovers – and how the needs of those on the inside don’t often coincide . . . In its best moments, Drybread contains what Marshall achieves in his stories, and the narrative pace fluctuates from a thriller to a love story.' Kevin Rabalais, NZ Listener

Owen Marshall: Selected Stories, edited and introduced by Vincent O'Sullivan, was published in 2008 (Vintage). Steve Scott writes in the New Zealand Herald: 'This collection marks three decades of work in which Marshall has dedicated himself to bringing New Zealanders stories about themselves . . . Flipping through the pages of this beautifully prepared edition and reading old favourites is a joy. For those who have not yet read him, this is the perfect opportunity to become acquainted with the master story-teller - nobody tells our stories better.'

Marshall also contributed a short story to The Best of New Zealand Fiction. Volume Three (Vintage, 2006), and edited The Best of New Zealand Fiction. Volume Five (Vintage, 2008).

He was President of Honour of the New Zealand Society of Authors in 2007/2008, and in 2007 became the inaugural recipient of the NZSA and Woolaston Estates Writers' Residency in Nelson.

In Essential New Zealand Short Stories (Random House NZ, 2009), Marshall gives a sampler tour of works by celebrated New Zealand writers: including the likes of Katherine Mansfield and Frank Sargeson, and fresh young talent such as Eleanor Catton and Craig Cliff. There could be no better guide to short New Zealand fiction than Owen Marshall, who many describe as New Zealand's best living writer of short stories.

In 2009, Marshall also edited Best New Zealand Fiction #6, in which he introduces exciting new names and showcases recent work by some of our top writers. In this volume, characters face such issues as redundancy, global warming, leaky homes and over-population, but deal with them in quirky, moving, humourous and shocking ways.

In Living as a Moon (Random House NZ, 2009), we see a new collection of the writer's short stories. The collection is rich with people exploring their own identities, and how they are affected by others. Set in both Europe and the Antipodes, the twenty-five stories are at once arresting, moving, funny and full of insight into the human condition.

Marshall was awarded with the Antarctica New Zealand Arts Fellowship (2009/2010). The programme seeks to increase understanding of Antarctica and its international importance through the work of New Zealand's top artists. His collection of poems, Sleepwalking in Antarctica and Other Poems, was published by Canterbury University Press in 2010.

Owen Marshall contributed to Timeless Land (Random House, 2010). Timeless Land is a collaborative book, and features work from two other New Zealand talents: painter Grahame Sydney and poet Brian Turner. The work has grown out of their appreciation for the landscapes of the Central South Island. It is the fourth edition of a much-loved and distinguished book, first published in 1995.

He was interviewed by John McCrystal in the anthology, Words Chosen Carefully, edited by Siobhan Harvey (Cape Catley Ltd, 2010).

His novel, The Larnachs, was published by Vintage in 2011. Kelly Ana Morey reviewed the novel in the NZ Herald, 'The Larnachs is a thoughtful, tender love story with...an awful lot of lovely, restrained writing by Marshall.' The following year, in 2012, Marshall became a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM).

Owen Marshall served for many years as a New Zealand Book Council Board member.

In 2013, Marshall received the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement for Fiction. The same year, he was the Henderson Arts Trust artist in residence at Henderson House, Alexandra.

In 2014, Marshall published his novel Carnival Sky (Vintage by Random House), and a book of poetry, The White Clock (Otago University Press).

Marshall was selected as a judge for the 2015 National Flash Fiction Day competition, which celebrates the shortest form of fiction on the shortest day of the year in New Zealand. He was also selected as a judge for the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards in the Fiction category.

In 2016 Marshall was a member of the judging panel for the Janet Frame Memorial Award for that award's final year , was an inaugural Fellow of the Academy of New Zealand Literature and published his novel, Love as a Stranger (Vintage by Penguin Random House), which was shortlisted for the 2017 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Radio New Zealand described the book as 'incredibly well crafted, and as is traditional with Owen Marshall every single world is placed perfectly'. Helen Speirs from the Otago Daily Times noted that the 'deft hand of one of New Zealand’s finest writers is everywhere in this deceptively simply told story of one woman’s transgression and one man’s unravelling. As the novel moves towards its climax the question is not if or when it will all end, but how.'

Marshall was awarded the 2017 Visiting Artist Scheme at Massey University.

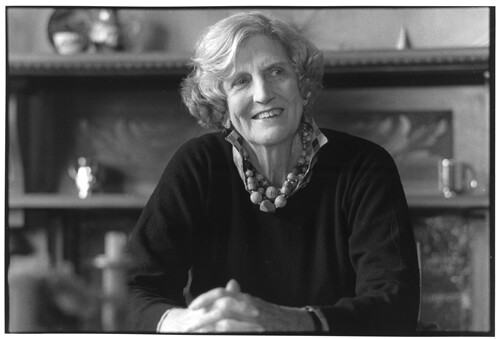

Author photo credit: Liz March

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Owen Marshall’s website

- Owen Marshall interviewed on Radio New Zealand

- Book readings on Radio New Zealand for: The Lanarchs and Love of a Stranger

- Owen Marshall's profile and interview on the Academy of New Zealand Literature website

- Reviews for Love as a Stranger (2016) on Stuff, Booksellers NZ, The Spinoff, and by Maggie Rainey-Smith

- NZATE Is this for credits? podcast interview (2022)